_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

BUONCONVENTO

Buonconvento2.pdf version for downloading and printing (9 pages - includes Piana, Castiglione del Bosco, Murlo and the Cuna Granary)

A small town on the via Cassia of some – albeit moderate – interest, on the way to other major sights (Pienza, Montepulciano, Montalcino, Monteoliveto).

Just over half an hour from Barontoli, via a pretty route over the hills. Go through San Rocco towards Grosseto. After about 8 km turn left towards Fontazzi. Go through Fontazzi to Casciano di Murlo and turn right at the T-junction towards Vescovaldo di Murlo. After about two kilometers, turn right towards Vescovaldo di Murlo and SS 2 Cassia, and continue following signs to Vescovaldo di Murlo. When you reach Vescovaldo, drive through the village and start following signs to Buonconvento.

Gate into Buonconvento ( Wikimedia)

Buonconvento lies on the Via Cassia at the confluence of the Arbia and Ombrone rivers and has long been a transit point on the Siena-Rome road. It also lies on a fertile plain and was a successful market town for surrounding farmers. Its main claim to fame is that the Holy Roman Emperor died in Buonconvento in 1313 shortly after capturing the town.

The town is surrounded by 14th century walls (much restored; the town took a big knock in the Second World War). One fine gate remains, the Siena Gate on the north of the town, with magnificent wooden doors. In side, there is a tiny historic centre (‘centro storico’) boasting a mini medieval town hall complete with coats of arms on the front and a small tower modelled on the Mangia of Siena.

Coats of arms on the Town Hall

A few doors further long, in the Palazzo Ricci, a small museum has been installed, as usual collecting together the works of art from surrounding churches. The top floor has the earliest stuff – including some not very exciting possible Duccios and Lorenzettis; a pretty-pretty Virgin and Child by Sano di Pietro; an attractive Botticelli-style Virgin and child with angels by Matteo di Giovanni; and an interesting collection of early metalwork. The next floor down contains the 15th century paintings, including a polished rendering of the Virgin feeding the Child by Il Brescianino, more metalwork and a good small collection of ancient vestments, including a most frivolous brocade cope made in Venice in 1771 covered in colourful swans, boats and little castles. The bottom floor demonstrates all that is worst in Sienese 17th century painting with works that are florid and sentimental, full of saints casting their eyes to heaven. There is, however, a splendidly naive statue of an unnamed pope at the far end.

The Palazzo Ricci is not without interest because of its unusual (for Italy) English ‘Liberty’ style decor, a conceit of the person who inherited the house in 1908. The staircase has some good designs, and on the top floor a bathroom of the period has been preserved.

The nearby church of Saints Peter and Paul (1450, redone in the 1700s) is of little interest as a building, but has managed to hang onto a couple of attractive paintings. On the right thrre is a Virgin and saints by Pietro Oriolo and on the left a Virgin and child with angels by Matteo di Giovanni.

Just outside the Siena Gate, round to the right, there is the Museum of the Mezzadria, in an old farm building abutting the city wall. Mezzadria was the share-cropping system that prevailed in the Sienese countryside until the 1950s, when it collapsed as more and more of the peasant farmers deserted the countryside for a better life in the towns. The landowner (padrone) would live in a castle or grand villa, and his land would be divided into farms or poderi (singular podere) with a casa colonica for the peasant farmer (contadino) and his family. The poderi could be large, as they often accommodated several generations of the same family, or e.g. several brothers and their families. The ground floor was usually for the animals with the family living on the floor or floors above. There could also be a hay-barn or fienile, easily recognisable by the wide spacing of the bricks to allow the circulation of air (the fienili are increasingly being converted to residences). The podere could be anything between 10 and 60 hectares. The farmer did not pay rent but could keep only half his crops; the rest belonged to the landowner. The estate was run by a fattore, a factor or bailiff, based in the fattoria. The latter was a large establishment often of many buildings, including olive oil press (frantoio); store-rooms both for the olives before pressing and the oil (which was kept in large terracotta jars); a wine cellar (tinaio); a large granary (granaio); a big kitchen with an oven for baking bread; a canteen and pantry etc., as well as an office and accommodation for the fattore and his family. The system needed policing and a guardia ensured that the contadini delivered up their crops and did not cut down trees or hunt game in the woods, which were the preserve of the landowner.

The museum has many photographs, stories and artefacts from that period and there are good explanations in Italian, but very little in English.

2005; revised 2013 and 2016.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PIANA

A tiny fortified church and a large fortified granary. Worth a very small detour.

A few kilometres along the road from Buonconvento to Vescovado di Murlo there is a turning to the tiny hamlet of Piana (on the Via Francigena), which has a very ancient parish church or pieve, dedicated originally to the Holy Innocents massacred by Pilate and now called Sant’Innocenza. The church is not open, but is in a lovely lonely spot on a spur, perfect for defence.

The entrance to the tiny fortified church

The Church was built in the 11th century austerely of brick and stone. It was strongly fortified between the 13th and 14th centuries against Florentine troops and marauding private armies. The site became what amounts to a brick-built fortress with the church as one of the sides. The Bishop of Siena is said to have taken refuge there in times of civil unrest. The buildings have been much altered over the centuries, and a campanile and pretty courtyard with wellhead were built in the 16th century when less warlike times prevailed.

Courtyard at Pieve di Piana

Grancia di Piana

Opposite the little road that leads up to the church there is a group of buildings known as the Fattoria di Piana (a fattoria is a sort of cross between an estate office and a home farm on a big estate). The estate belonged to the Tolomei family in medieval times and was donated to the Hospital of Santa Scala by a Tolomei who was the rector of the hospital at the time. At the end of the 14th century, the Hospital built a grancia or granary there, subsidiary to the enormous one at Cuna (on which see below), to store wheat for supplying the hospital’s huge establishment in Siena.

North side of the Grancia (granary) di Piana

The buildings of the fattoria are now either deserted or have been turned into villas and appartments. If you go up between the two groups of buildings, you will find a tiny red-brick baroque church, and the granary is the huge building to the left of it. Two wings were built onto the south side at some point when it was turned into a villa. But the north side remains in its original form and there is an attractive avenue of cypresses leading up to the north doorway. It is an impressively fortified stone building with slanting buttress sides, as befits dangerous times. As so often with Sienese medieval buildings, the wall is scattered with crests, probably of the various hospital rectors.

Baroque church at the Fattoria di Piana |

Cypress alley leading from granary

|

More information on the fattoria (in Italian) at

http://archeologiamedievale.unisi.it/santa-cristina/la-fattoria-di-piana

2016

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CASTIGLIONE DEL BOSCO

An agricultural settlement that has been turned into a five-star hotel, whose tiny chapel has the last authenticated work of the great Sienese painter Pietro Lorenzetti.

The road to Castiglione del Bosco is well signed and turns off the Buonconvento-Casciano di Murlo road about 10 kilometres north of Buonconvento. After the turn-off, the road quckly becomes an unpaved “strada bianca” (white road). After another 5 kilometres or so, well-watered and aggressively green golf courses appear on either side. The very discreet and unmarked entrance to the hotel is a little further along on the left. The road goes on to Montalcino, but is not recommended as it is extremely tortuous and slow – it is better to go back to Buonconvento.

The ruined castle is in the background and the campanile of the chapel on the right.

Castiglione was a strong point with a castle in the middle ages, but the castle fell into ruins (part of which can be seen today) and for the last few centuries the place has been no more than the centre of a large agricultural estate, with a number of old buildings. The estate is in the Montalcino wine-growing area and was one of the pioneer producers of that city’s “Brunello di Montalcino” – a wine that was developed only at the beginning of the last century. In 2003, a member of the Ferragamo family acquired the property and turned the whole thing into an extraordinary 5-star hotel in the middle of nowhere (it is only accessible along a winding dirt track) with fantastic views on all sides. It is more a luxury village than a hotel with the accommodation spread out over a number of villas.

For art-lovers the attraction is the tiny chapel of San Michele (ask at the reception to see it), which dates back to the time when Castiglione was a working fortress. A fresco painted by Pietro Lorenzetti in 1345 (shortly before he died in the Black Death) covers the end wall. The guides say that the central panel portrays the Annunciation. But it seems more likely that it is a representation of the Angel who according to legend came to warn the Virgin that she was about to die, as the angel is carrying a palm rather than a lily and the Virgin looks rather mature (Duccio painted a similar scene). The saints on either side are Anthony Abbot, John the Baptist and Stephen on the left; and Michael the Archangel, Bartholomew and Francis on the right. Michael the Archangel is traditionally the Harbinger of Death, so a scene foretelling the Virgin’s decease may well have been chosen because the church is dedicated to St Michael. The fresco was rediscovered only in 1876.

Fresco by Pietro Lorenzetti at Castiglione del Bosco

2013, revised 2015.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MURLO: ETRUSCAN MUSEUM

A small museum (Antiquarium di Poggio Civitate) in the little fortified village of Murlo (on the way to Buonconvento from Barontoli) with the Etruscan remains dug up from an archaeological site nearby; not worth a special expedition, but worth popping in if you are passing by.

Open mornings and afternoons except Monday

Entrance to the fortified village.

The nearby archaeological site is on a small hill called Poggio Civitate which was a flourishing Etruscan settlement 800-500 BC. The museum is housed in two old ancient palazzi, the largest of which (known as the Palazzone or “big palace”, although it is only big in the context of the tiny village) used to be used in medieval times by the Bishop of Siena. There are panels with explanations translated into particularly fractured English, but unfortunately the individual objects have few labels.

The first floor has remains from a 7th century BC villa and nearby workshop that were burned down in about 600 BC forcing the inhabitants to flee, leaving jewellery etc. behind. The remains are not particularly exciting and mostly in small pieces. Their main interest is that they are so ancient, from the Etruscan “orientalising” period – this was long before the Romans and even early in terms of Greek civilization (with which there is evidence of trade). Part of a roof has been reconstructed with the remains of old tiles, showing a technique almost identical to that used in Tuscany today.

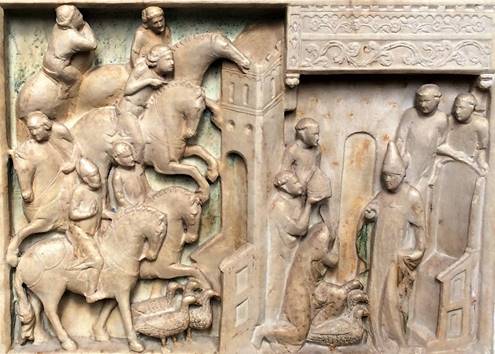

The second floor has remains from a grander 6th century BC villa in the slightly later “archaic” style. It was built to replace the earlier villa but then abandoned and deliberately buried in about 525 BC for some unknown reason. Here also the best thing is the re-creation of part of the roof, the ridge of which is decorated with terracotta statues, including one of a seated man wearing a wide-brimmed cowboy hat. The remains of several of these arresting figures were found, and they are unique to Murlo. There are also gargoyles and sphinxes, and friezes of stamped terracotta tiles under the eaves, showing banqueting scenes, processions and horse-races (perhaps an early version of the Palio), complete with the large cup awarded to the winner.

A Murlo cowboy

The third floor has remains from other nearby sites, mostly of lesser interest, although there are intriguing small bronze figurines of wrestlers. The Etruscans were good at metalwork. By the car-park outside the village, there is a small display of Etruscan bronze-casting tecniques.

2003, 2016

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE CUNA GRANARY(GRANCIA DI CUNA)

A large, rare and well-preserved fortified medieval granary, little visited by tourists. In 2018 it was closed for restoration and seems likely to remain so for some time, so it would be wise to check with the Siena tourist office before visiting.

Cuna is off the via Cassia (SS2 - the Siena-Rome road) just north of Monterone d’Arbia. Coming from Siena, after Isola d’Arbia, Ponte a Tressa and Le More, keep right on the old road towards Monterone. Cuna is up a little road to the right; you will see the huge brick-built granary on the hill above.

For an alternative route making for a really spectacular drive from Barontoli (with some untarred stretches), go through San Rocco and onto the Grosseto road. Turn left where signed to Grotti. Go on through Grotti to Le Ville di Corsano. At the entrance to the village, turn right towards ‘Pieve di San Giovanni Battista di Corsano’ (an attractice Romanesque church, rarely open). Go on down this road, ignoring the turn-off to Radi, until signs to ‘Cassia SS2’ start appearing. Follow these across fantastic countryside until you reach the Via Cassia, north of Monterone d’Arbia, and then follow the instructions above.

The Romanesque Pieve (parish church) di Corsano

The granary was built by the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena – see the Hospital’s symbol of a ladder (scala) surmounted by a cross above the gate. The hospital – a massive undertaking – originally acquired land here in the 1100s. They built the original granary and the neighbouring church of Sts James and Christopher (Giacomo e Cristoforo) in 1314, a period of military instability, in order to safeguard their supplies of grain. Over the centuries, various changes and additions were made, including the construction of a ramp in the 18th century so that mules could carry grain up to the upper chambers of the granary. It has survived reasonably intact since then. This may be partly because, after it ceased being used as a granary, local families took up residence in many of its various chambers and remain there to this day – glimpses of washing lines and smells of cooking greet those mounting the ramp. The authorities have made the best of the situation by classifying the whole building as a street, with official street numbers outside the dwellings. They have named the street ‘vicolo Beato Sorore’ after the legendary founder of the Hospital.

Entrance to the Cuna granary.

One enters the complex through gates in the double line of defences and can then wander up the ramp. Unfortunately, the old granary chambers that have not been taken over as dwellings are closed because of structural dangers, but one can nevertheless obtain a good impression of the hugeness of the complex and the sophistication of the defences.

The church (the key of which can be obtained at house No.13 to the right of it) has the usual remains of 14th century frescoes, white-washed over and then rediscovered, some as recently as the 1990s. The most interesting are the ones on the left of the entrance. The large painting of two saints represents St Ansano (an obscure saint who was an early patron of Siena) and St James. Below are two tiny scenes showing the “Miracle of the hanged man”. On the left some pilgrims are having a meal and a man is making off with a loaf of bread. The wrong man was caught and hanged and the right hand scene shows St James rushing in, superman style, to save him by holding up his feet. Originally, the whole church would have been covered in frescoes.

(2005 and 2013)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MONTALCINO and SANT' ANTIMO

Montalcino and SantAntimo.pdf version for downloading and printing (5 pages)

A steep-streeted medieval hill town of moderate interest, but with a most beautiful Romanesque abbey nearby.

Montalcino

Turn right off the SS 2 (via Cassia) just South of Buonconvento. The best car-park, if there is space, is right up the hill in front of the Fortezza.

Photo wikimedia

Montalcino has all the required attributes of a Tuscan hill town: fortress, medieval town hall with tower; irregularly shaped central piazza; art gallery; Duomo. But none is outstanding – although the art gallery has recently been modernised and is now one of the best set out in the Senese. Historically, the town’s main claim to fame is as the place to which 700 leading Sienese families fled in 1555 when Siena finally submitted to the French and Florentines. They stayed for four years, flying the black and white flag of Siena, until Montalcino also submittted to Florence. Now, Montalcino is a wine and honey town, famed for its ‘Brunello’ wine, which is on sale in every other shop in the town.

Even by Tuscan standards, the streets of Montalcino are extremely steep. The town is built on a slope along the side of a ridge and the main arteries run parallel to the ridge from the Fortezza in the north to Piazza Cavour in the south. Tiny, almost vertical lanes or steps run between them. Unfortunately, the map supplied by the Tourist Office is wholly inadequate with almpost no names of either places or streets, but the town is small enough for it to be fairly easy to find one’s way around.

Fortezza and San Agostino

The fortress (Fortezza, Castello or Rocca, open 9-13 and 14.30-1) is impressive. The ramparts were built by the Florentines after they took control of the town, and there are the usual extensive views from them. The way up to the ramparts and the small museum in the Fortezza is through the wine-bar (enoteca) on the ground floor; tickets can be purchased from the bar.

From the Fortezza, one can go down via Ricasoli to the 14th century church of San Agostino on the right. Its elegant Gothic marble doorway has a nicely discreet touch of Sienese black and white stripiness. The interior (with some rather damaged frescoes) is now part of the Civic and Diocesan Museum and is entered through it.

Civic and Diocesan Museum

Just up the road to the left, at No 4, is the recently renovated art gallery, the Museo Civico e Diocesano. It has a small collection of mainly 13th to 15th century Sienese painting and a particularly good collection of early painted wooden statues, cleverly interspersed with modern painted terracotta figures by a local artist inspired by the mediaeval pieces.

On entering, on the right in Room A, there is a good polyptich by Bartolo di Fredi (1330-1410) of the Coronation of the Virgin. Like most of this artist’s work, it is extremely colourful and full of incident, including musician angels and scenes of the life of the Virgin. The room contains two other paintings by Bartolo di Fredi: a Virgin and Child on the wall facing the door, and a tryptich of the Deposition to the left of the door (note the side panels showing a local holy man curing somebody and then levitating). Also in this room are two wonderfully stiff and mannered, life-sized, painted wooden statues of the Virgin and the Angel Gabriel dating from the 1300s, the same period as the paintings.

Room B has yet another life-size pair of statues representing the Annunciation (there are three altogether in the museum). There are also a painting of the Virgin and Child by Simone Martini (c1284-1344) to the left of the door, and panels representing St Peter and St Paul by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c.1290-1348) to the right of the door. It also harbours no fewer than four early 14th century sculpted crucifixes – the one beside the Simone Martini is the most striking, with its tortured face (the one on the opposite wall has cast up eyes reminiscent of Guido Reni at his most sentimental). And in the middle of the room there is a really splendid statue of St Peter and his keys dating from about 50 years later. The large painting of Doubting Thomas at the far end of the room is also worth a look. He is alleged to have doubted whether the Virgin really was assumed into Heaven, and he is being shown her tomb, empty apart from some flowers, while above the Virgin ascends and lets drop her belt to Thomas as a sort of souvenir. Don’t miss the huge 14th century semi-monochrome fresco of the crucifixion, high up on the wall, by a pupil of Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

Room C has on the left of the entrance a charming “Virgin of Humility” by Sano di Pietro (1406-1481) – very simple with no throne or lavish pavement but just a few roses and some discreet hovering angels above.

Room D contains two wonderful Andrea della Robbia terracottas. The first is a 1507 panel of the Virgin and Child between two saints – St St Peter on the right with a set of particularly large and ornate keys. All the figures have wonderfully serene expressions. In a corner there is an equally excellent statue of St Sebastian.

There is little of interest downstairs, but the upstairs rooms (some still to be filled) are worth a brief glance. Room M has some of the earliest known works of Sienese art, including an icon-like Madonna and a crucifix, both dating back to the end of the 12th century.

Piazza del Popolo

Down the hill behind San Agostino, a choice of a road or steps through a tunnel leads down to the diminutive main square, the Piazza del Popolo. It is dominated by the mediaeval town hall, the Palazzo del Popolo, complete with tower and family crests of mediaeval mayors. In the arcade beneath the tower there is a 16th century statue of Cosimo I, the Grand Duke of Tuscany at the time of the Florentine take-over, no doubt commissioned to mark that event. There is a cafe under the pretty 14th century loggia on the other side of the square that makes a good place for a coffee-break.

Santa Maria della Croce and San Francesco

From Piazza del Popolo, via Mazzini leads down to Piazza Cavour, on the opposite side of which a building that used to be the hospital of Santa Maria della Croce. It has been appropriated by the town council for its offices, but just inside the door on the right (No. 15) there is a window (with a light switch underneath) through which one can peer into the old pharmacy of the hospital. Its walls are covered in charming frescoes by Vincenzo Tamagni, painted in 1510. Opposite the window the Virgin sits enthroned with St Jerome and his lion on the left and St Augustine on the right – as Doctors of the Church, both are engaged in reading or writing. To the sides there are trompe l’oeil cupboards and figures in niches.

The church of San Francesco, further down the slope to the north-west of Piazza Cavour, is permanently closed, and all the best things in it have been removed to the museum. The cloister next to it is now part of the local hospital.

******************************************************

Sant’ Antimo

The church is usually open to visitors from 10-12.30 and 15-18.30. The monks are specialists in Gregorian chant, and it is sometimes possible to sit at the back to listen to them chanting the Offices at 12.45, 14.45 and 19.00 (18.30 on Sunday). There is also a Gregorian Mass at 11.00 on Sundays.

This abbey church, one of the oldest and most beautiful in Tuscany, is about 10 km to the south-east of Montalcino, well sign-posted with yellow signs. It is set in a grove of olives and cypresses just below the village of Castelnuovo del Abate (the olive trees include some of the few survivors of the great frost of 1985 that killed almost all olive trees in Tuscany down to ground level; they were at first thought to be completely dead, but then sprouted branches from the roots which explains why most now look like bushes rather than trees). Until 1979, the church was deserted, the abbey buildings having long since disappeared. But now a small group of monks has come back, living in the building to the right of the church.

The abbey was founded by Charlemagne when he conquered Tuscany in the 8th century. The legend is that his army, returning from Rome, were struck by an epidemic when they got to this spot. The church was the fulfilment of a vow made by Charlemagne to found an abbey there if the sickness stopped, which it did thanks to an angel appearing with a magic herb. But all that remains of the Carolingian church is its apse (to be seen on the outside next to the main apse) and the crypt. The present church was built in around 1118 of wonderful pale honey-coloured stone. Originally the abbey was extremely rich, benefitting from bequests from the pilgrims who stopped there on their way to Rome. But the Sienese took a large chunk of the abbey’s territory when they sacked Montalcino in 1212; the bequests dried up; one of the abbots was imprisoned for villainy; and in 1462 Pius II closed it down. It has remained gently decaying since then.

The exterior is dotted with ancient carvings of fantastical animals, although some of the best are unfortunately round the door on the right-hand side of the church which has now been closed off to accommodate the monks. Particularly unusual for that early period is the panel with a Virgin and Child at the base of the tower. The facade was never finished (owing to funds running short), and there was obviously uncertainty as to whether to have a double or a single door. The original ornate porch has not survived, although the lions on which its pillars rested are just inside the door.

Inside, there is a marvellous feeling of light and height. The church is built in a French-style Romanesque basilica pattern, with elegant and interesting capitals; note in particular Daniel in the lions' den above the second column on the right (with two lions eating each other simultaneously on the other side). The deambulatory behind the altar is one of the most beautiful parts of the church, several of the columns or their bases being of alabaster or onyx, translucent when the sun - or a torch - shines through them. When the Piccolomini Pope Pius II suppressed the abbey in 1462 and made it part of the diocese of Montalcino, he rubbed in his dominance by leaving his half-moon crest all over the place, for instance on the flag-stones round the altar. The carved stones round the door into the sacristy (on the right) are supposed to have come from the original Carolingian church. The sacristy itself (rarely open) is in what remains of the Carolingian building; it is covered in 15th century grisaille frescoes of the life of St Benedict.

The church contains two ancient and beautiful wooden sculptures: a stark and tragic 12th century crucifix over the altar (unfortunately often difficult to see against the light from the windows in the apse) and a 13th cenury Virgin and Child in a glass case on the right. Beneath the altar is a small crypt with a fresco of the Pietà. The slab that forms the top of the altar in the crypt is a bit of recycled Roman marble.

The exterior is dotted with ancient carvings of fantastical animals, although some of the best are unfortunately round the door on the right-hand side of the church which has now been closed off to accommodate the monks. Particularly unusual for that early period is the panel with a Virgin and Child at the base of the tower. The facade was never finished (owing to funds running short), and there was obviously uncertainty as to whether to have a double or a single door. The original ornate porch has not survived, although the lions on which its pillars rested are just inside the door.

Inside, there is a marvellous feeling of light and height. The church is built in a French-style Romanesque basilica pattern, with elegant and interesting capitals; note in particular Daniel in the lions' den above the second column on the right (with two lions eating each other simultaneously on the other side). The deambulatory behind the altar is one of the most beautiful parts of the church, several of the columns or their bases being of alabaster or onyx, translucent when the sun - or a torch - shines through them. When the Piccolomini Pope Pius II suppressed the abbey in 1462 and made it part of the diocese of Montalcino, he rubbed in his dominance by leaving his half-moon crest all over the place, for instance on the flag-stones round the altar. The carved stones round the door into the sacristy (on the right) are supposed to have come from the original Carolingian church. The sacristy itself (rarely open) is in what remains of the Carolingian building; it is covered in 15th century grisaille frescoes of the life of St Benedict.

The church contains two ancient and beautiful wooden sculptures: a stark and tragic 12th century crucifix over the altar (unfortunately difficult to see against the light from the windows in the apse) and a 13th cenury Virgin and Child in a glass case on the right. Beneath the altar is a small crypt with a fresco of the Pietà. The slab that forms the top of the altar in the crypt is a bit of recycled Roman marble.

Restaurants

Montalcino is a bit of a gastronomic centre, and most restaurants are reasonably good. In the town, there is a clutch of good value trattorie on via Ricasoli near the Fortezza. There are also two slightly smarter restaurants down via Mazzini from the Piazza del Popolo, the Taverna Grappolo Blu and Il Moro. In the little village of Castelnuovo dell’Abate next to San Antimo there are also couple of simple trattorie.

(1996, with some revisions in 2010)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ABBADIA SAN SALVATORE

Abbadia San Salvatore.pdf version for downloading and printing (2 Pages)

A small town on the slopes of Monte Amiata, with the remains of a Lombard church.

Monte Amiata, a dead volcano, is at some 6000 feet the highest mountain in Tuscany and visible from Barontoli. Abbadia San Salvatore is on its eastern slopes and, in winter, serves as a ski resort. Otherwise, its main claim to fame is its abbey, the "Abbazia San Salvatore", or rather the church's eighth century crypt. Follow the yellow signs to the Abbazia from the town centre.

The abbey church

According to legend, the original abbey church was built by the by the Lombard king Rachis in the year 745. He was hunting in the area, and saw a vision of Jesus, the Holy Saviour (San Salvatore). As a result he got religion and felt impelled to build a Benedictine monastery on the spot. His original church, or what remains of it, is now the crypt of the present church. It is a fascinating early survival - one of the earliest churches in Italy outside Rome and Ravenna. Its strange carved columns (some designs reminiscent of Celtic art) and capitals covered in the heads of men, rams and oxen look more pagan than Christian, and the whole atmosphere is of great ancientness.

The original church, now the crypt

In 1035 the present Romanesque church was built on top of the earlier church, and the monastery soon became one of the most powerful in Tuscany. The Romanesque church is a satisfyingly simple structure, single-aisled and built of good chunky ashlar stone. Inside on the right wall there is a superb 12th century crucifix. Instead of the usual hanging head, Christ clearly still belongs to the living, expression serious but serene, eyes gazing straight at the beholder, mouth open as if about to speak. At the other end of the church there are a number of frescoes by the 17th century artist Francesco Nasini - the best is the royal boar-hunt on the right.

Next to the church are the remains of a 16th century cloister. From one corner of the cloister, a metal staircase leads up to a small museum, which one of the monks will usually open if asked (on leaving, we usually make a small donation). The museum contains one of the wonders of the textile world, an eighth century red silk cope (priestly garment) of Persian manufacture, probably booty from a crusade. It is not terribly exciting for the non-expert, but its age and good state of preservation make it remarkable to textile freaks. It used to be covered with seed pearls, with patterned cloth round the hem, but nothing remains now but the plain red silk, albeit with elaborate patterns in the weave. A small piece of the patterned cloth from the hem, woven in four colours, is displayed separately in a frame - rather unreligiously, it is covered in figures of dancing girls and huntsmen.

The museum also contains a small eighth century Irish reliquary (goodness knows how it came to San Salvatore), and a handsome gilt reliquary bust of the fourth century Pope St Mark, this last object dating from 1381. It was recently restored, and two pieces of mediaeval cloth found inside it during the restoration are displayed on the wall.

June 1995

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SAN QUIRICO D'ORCIA

San Quirico.pdf version for downloading and printing (5 pages)

An unspoilt small town with a beautiful Romanesque church and no tourist razzmatazz. Town plan available from tourist office opposite the Palazzo Chigi in the main street. Also worth visiting briefly are the nearby Bagno Vignoni, Rocca d’Orcia and Castiglione d’Orcia.

This little town, half-way between Montalcino and Pienza, is usually by-passed by tourists; yet it contains several lovely things. Situated on what was one of the main roads between the Northern Italian states and Rome - indeed one of the main pilgrims' ways to Rome (the via Francigena) - it used in the past to be a major stopping place for important people on their way south. The first recorded distinguished traveller to stay there was an early Archbishop of Canterbury, Sigeric, in 990. The most famous visitor was the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, who camped there in 1154 when on his way to Rome to be crowned by the Pope, and there is still a festival every year in honour of his visit, the "Festa del Barbarossa", on the third Sunday in June.

San Quirico still has much of its original fortified walls, with traces of some 14 small towers and three gates - the best preserved is the Porta Cappucini, a strange polygonal structure. But the town’s main sights are three attractive churches, strung out along the main street.

The Collegiate Church (Collegiata), the best of the three, is the first that you come to on entering the town from the direction of Siena. It is an attractive Romanesque-turning-to-Gothic structure dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, with three excellent carved doorways. The striking main door, which greets and draws on the visitor entering the town, is pure Romanesque and is attributed to Giovanni Pisano. It is carved mainly of white travertine, but some of the animals and pillars are of a darker, brownish stone, unfortunately softer and therefore more worn. The two crocodile-like dragons over the door, however, are still excellently preserved. There are two other intersesting doors on the side of the church, which show signs of the transition to Gothic, but the middle one in particular still has much interesting carving, with figures attributed again to Giovanni Pisano. Note also the tiny figure carved in the corner of the window on this side.

Side doors of the Collegiata

Inside, the Romanesque interior is somewhat marred by an awkward baroque altar. But the church contains two treasures, a tryptich (1470) by Sano di Pietro, and quite magnificent marquetry stalls. The tryptich (light switch on the left) shows the Virgin and Child surrounded by saints; St John the Baptist and San Quirico on the left and St Fortunatus and St John the Evangelist on the right, and two tiny donors below. According to one legend, a Jew called Kyriakus revealed the hiding-place of the true Cross to St Helena, and he holds the nails from the cross (this is all a bit curious, as the more standard story of San Quirico is that he was a child martyr, so not the sameperson at all). Despite these gory symbols, and the head on a plate carried by St Fortunatus, the figures have a quiet and serene look. Note also the sumptuous robes of the Virgin and the decorative marble floor with a carpet under the throne.

Another high-light of the church, however, is the set of the magnificent inlaid panels behind the altar, originally from Siena Cathedral. They date from between 1482 and 1502 and are by the Sienese artist Antonio Barili. There are seven scenes, all with great character, some of the best examples of the Italian art of "painting" with wood. Unfortunately, the altar area has been roped off and the stalls can only be seen by stepping illegally over the rope

Also worth a glance, on the left of the nave, is the handsome marble tomb of another visitor to San Quirico, this time one who died there, in 1451 – the German Count Henry of Nassau, who died here while on his way to Rome in 1451.

Next to the Collegiata, the Palazzo Chigi is a fine if dilapidated 17th century villa built by Cardinal Flavio Chigi, a nephew of the then Pope, to whom the Grand Duke Cosimo III Medici of Florence (who had himself recently taken possession of the town) had granted the Marquisate of San Quirico (the sort of thing that happened to papal nephews). Further down the main street, also on the left, is another church, San Francesco (also known as Chiesa della Madonna). It has been messed about with architecturally and its interior is now elegant Renaissance in style. It has a rather beautiful white terracotta Madonna on the main altar, attributed to Andrea della Robbia - it may be part of a pair making an Annunciation scene, as it is rare to see the Virgin alone without the child unless she is either meeting the archangel Gabriel or being assumed into heaven. There are also two 15th century painted wooden statues - this time a complete Annunciation set, with both the Virgin and the angel - attributed to a pupil of Jacopo della Quercia.

Opposite San Francesco, there is a way through into the Horti Leonini (Leonini Gardens), a good example of a formal 16th century Italian garden.

Horti Leonini with the statue of Grand Duke Cosimo.

The gardens were created in 1580 by one Diomede Leoni for the comfort and convenience of the noble travellers who passed through San Quirico (an American writer, Patricia McCobb, has written a book about the creation of the garden). There is usually an exhibition of modern sculpture dotted around the garden, but also one older and permanent statue in the middle, of Grand Duke Cosimo Medici III of Florence, sculpted in 1688 by Bartolomeo Mazzuoli on the orders of Cardinal Flavio Chigi (no doubt as a thank you gesture for the Marquisate that Cosimo had just bstowed on the cardinal). Open daily 09.00-20.00 March-October, and 10.00-17.00 in winter.

At No. 38 on the main street there is a gothic house where St Catherine of Siena was said to have resided during a stay in San Quirico. Further along the main street on the right, almost at the end of the town, is the tiny Romanesque church of Santa Maria Assunta (St Mary of the Assumption). It is very early, built probably at the beginning of the 10th century, and is an unspoilt example of the simplest sort of one-aisled Romanesque church, almost the only decorative feature being the tiny porch, said to have been originally destined for the abbey church of Sant’ Antimo, whose monks had run out of money.

Santa Maria Assunta

********************************************************

Bagno Vignoni

This village near San Quirico has been known for its thermal baths since Roman times. Hot mineral water wells up into a pretty pool in the centre of the village, and then descends to the various spa hotels and warm pools on the slopes below. The central pool is now out of bounds for bathing, but especially in the 14th and 15th centuries many distinguished visitors came to take the waters, including Lorenzo il Magnifico, the Sienese Pope Pius II Piccolomini and St Catherine of Siena. In those days there were separate bathing areas for men and women. The current large pool was the men’s area; the much smaller women’s pool was on the other side of the Renaissance arcade along the end of the pool. There are several cafés and restaurants around and near the pool, but they are rather chi-chi and it is best to eat in San Quirico.

**************************************************

Rocca d’Orcia

A little further south there is a tiny medieval village or “borgo” called Rocca d’Orcia, and above it a massive “Rocca” – a formidable and vertiginous medieval fortress built on top of a high rock, with no apparent entrance, visible for miles around, known as the Rocca Tentennano. This was one of the most important and impregnable strong-points on the via Francigena pilgrim route from Northern Europe to Rome. It dates back at least to the ninth century, although it has been much rebuilt over the ages. One can climb to the top of the fortress to obtain perhaps the most spectacular panoramic view in the whole of the Senese – a province of spectacular views. There is usually an exhibition of modern art in the vaulted room on the bottom floor of the fortress. A ticket is needed to get access; the opening hours (in 2013) are 10.00-13.00 and 15.00-18.00, every day in summer but only weekends in winter.

Rocca d’Orcia

******************************

Castiglione d’Orcia

Next to Rocca D’Orcia, there is a bigger village called Castiglione D’Orcia with a pretty central square. It is overlooked by the ruined Castello degli Aldobrandeschi, a rival to the Rocca. Recently, the Oratory of St John the Baptist in Castiglione has been opened as a small art gallery (Sala d’Arte) to house various paintings from the churches round about. The village is the home of the 15th century Sienese artist Lorenzo di Pietro (generally known as Il Vecchietta) and the collection includes a painting by him of the Madonna being crowned by Angels, unfortunately somewhat damaged in its lower portion. There is also a Virgin and Child attributed to Simone Martini and workshop (probably mainly workshop), recently retrieved from the museum in Montalcino; and a good Madonna nursing the Christchild by Giovanni di Paolo. Unfortunately, the gallery is only open at weekends at present.

There are various eating places in both Rocca d’Orcia and Castglione d’Orcia.

(1991 and 2013)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PLACES ALONG THE SIENA-GROSSETO ROAD

Grosseto Road.pdf version for printing and downloading (5 pages)

Grosseto is of very little interest, but there are some places worth visiting just off the road between Siena and Grosseto.

Bagni (or Terme) di Petriolo

An old spa with a sulphurous hot spring open to all

In a valley below a spectacular viaduct of the Grosseto superstrada, about 15 kilometres from San Rocco a Pilli and well sign-posted, there is to be found the old spa (with remains of 15th century walls) of Petriolo. All that remains today is a small (free) bathing pool where the bad-egg-smelling hot waters spill out into the river, and an establishment where one can pay to have serious treatment. The public bathing pool used to be rather a muddy affair and was overwhelmed by a landslide a few years ago; it has now been reconstituted in a much improved form. The water is really quite hot (43°C), not necessarily what one wants in high summer. There is also a smart spa hotel on the other side of the viaduct.

2003.

****************************************

San Lorenzo al Lanzo, also known as Abbadia or Badia Ardenghesca

Romanesque church of minor interest and along a bad road but in a beautiful valley

This abbey church is difficult of access and only for the enthusiasts as it is of fairly minor interest. From Petriolo, drive towards Paganico for about eight kilometres, ignoring the turn off to the SS223. Take the right turn to Civitella Marittima. After about three kilometres, there is a right turn to the monastery along a cypress alley.

From Paganico, take the road to Arcidosso and Castel del Piano, and turn off to the left along a pretty country road to Civitella Marittima and Abbadia Ardenghesca. After about nine kilometers, turn left onto a very bumpy dirt road (signposted) and then after a further four kilometers right. The abbey church is about a kilometre on, on the right, recognizable by the filled-in arches which originally separated the nave from the now demolished side aisles.

If approaching from the Grosseto road (SS 223), take the exit for Civitella Marittima. Coming from Grosseto, the abbey road is signposted almost as soon as you leave the slip road. If coming from Siena, go towards Civitella and almost immediately turn right onto the road signposted Siena that crosses onto the other side of the Grosseto superstrada, turning left before the slip road back onto the superstrada. Beware: between the Civitella exit and the abbey church there is a ford that can be a raging torrent in time of rain.

San Lorenzo is in a most beautiful wooded valley, with cypresses and umbrella pines (a good place for a picnic, except that it is almost below one of the spectacularly high viaducts over which the Grosseto road passes and there is a slight traffic roar). The church itself is closed, but there is an interesting travertine façade with capitals carved with fantastic beasts, including a one-headed two-bodied lion similar to that on one of the San Antimo capitals. A villa, usually deserted, has been built next to the monastery, probably on the remains of the old monastic buildings.

For those not interested in picnics, Civitella has a good restaurant, la Locanda nel Cassero, offering an interesting modern take on traditional Tuscan fare at very reasonable prices for the quality. It is right in the middle of the maze of narrow mediaeval streets of this typical hill village, however, and driving up into the village is a challenge, as is parking. The restaurant is closed on Tuesday, and also Wednesday lunchtime.

**************************************************

Paganico

Small town with church with interesting frescoes

Paganico is about 35 km from San Rocco a Pilli and is well sign-posted from the Grosseto road. It is a workmanlike small town or large village that used to be a defensive point on Siena’s southern borders, and still has most of its 13th -14th walls, built on the instructions of the Sienese Senate. It has little to offer the visitor except for the frescoes in its church, San Michele Arcangelo, which are among the best preserved and most beautiful in any small church in the Senese.

The church is in the main square, and from the outside could not be plainer. The frescoes are in the chancel, behind the altar – if the young parroco (parish priest) is there, he will let you walk behind the altar to see them better. They have been recently restored, revealing the name of an artist called Biagio di Goro Guezzi, dated 1368. On the left wall, on the top there is a delightful Nativity, with the Child rather unusually being washed. Below, the middle fresco is a splendid rendering of St Michael the Archangel casting the devil out from heaven. The picture on the left shows a legend in which St Michael appeared in Puglia in the form of a bull and some hunters tried to shoot him, only to find their arrows turning round and coming back at them. On the right, St Michael appears above Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome, delivering the city from the plague.

On the right wall, the upper scene is of the Adoration of the Magi. Below there is a Last Judgement, with the Virgin Mary giving souls a helping hand out of purgatory into heaven (the figure in green above is Wisdom); Archangel Michael in the middle; and the Devil on the other side, having collected only one soul compared to the many on the purgatory/heaven side; the Devil is clearly furious and is baring his teeth at the Archangel Michael (the parroco commented approvingly to us that this scene presents an optimistic picture of mankind). There are symbolic connections between the upper and lower scenes. For instance, although Michael is holding the baskets of the scales, the actual weighing is done by Christ and the chains can be seen going up to him. On the left hand side of the top scene, above the heavenly side of the Last Judgement, there are horses’ heads bowing to Jesus, whereas on the other side the horses have turned their rumps to Jesus, showing that those who accept Christ can expect heaven and those who reject him must expect hell.

To complete this wonderfully preserved series of frescoes, there is an Annunciation on either side of the window; the four evangelists in the vault and saints under the chancel arch.

There are three other good works in the church; a Madonna and Child by Guidoccio Cozzarelli (1450-1516) over the main altar; another Madonna and Child (about 1480) by Andrea di Niccolò (1445-1525) on the left wall; a huge and unfortunately damaged fresco of St Christopher on the right wall, and next to it, in a glass case over a side altar, an extraordinarily moving, not to say harrowing, painted wooden crucifix (15th century).

************************************************

Roselle

Interesting and extensive Etruscan and Roman ruins, little visited.

About 10 km north of Grosseto, well-signed from the Siena-Grosseto road (follow brown or yellow signs to “Rovine” or “Ruderi” (ruins) di Roselle, or to Parco Archaelogico – not those to Bagno Roselle, which is a small village some kilometres away). It is open from 8.30-19.00 between May and August, and closes slightly earlier at other times of the year. As it receives so few visitors, you may have the place entirely to yourselves.

Roselle was an important Etruscan town, sited on a strong point overlooking the lake that covered the plain where Grosseto now stands. It was founded around the 7th century BC. It was conquered by the Romans, however, in the 3rd century BC and substantially rebuilt over the next few centuries, so most of the buildings visible today are Roman. The most visible Etruscan remains are the impressive 6th century BC city wall, built of huge blocks of stone and extending to some 3 km.

The town retained its importance into the early Middle Ages when it was the seat of a bishopric. But it was pillaged by the Saracens in 935, the bishopric moved to Grosseto in 1138 and the town was gradually abandoned. As so often, people from local villages removed much of the stone for their own building purposes. In the 19th century, a British traveller in search of Etruscan remains, George Dennis, described it as “a wilderness of rocks and thickets – the haunt of the fox and the wild boar, of the serpent and lizard – visited by none but the herdsman or shepherd”.

Since then, it has been considerably tidied up by the archaeologists. None of the walls of the buildings is more than a few feet high. But the lay-out can still be clearly seen, as can the impressively paved streets. Quite a few broken Roman statues were found on the site. These are now in the museum in Grosseto, but rather hideous replicas, in Carrara marble, have been erected at random points around the site.

From the entrance, turn up to the left to the main part of the city (if you turn right, you are in for a long walk along the Etruscan walls and it is best to do this at the end).

You can go along the modern path up to the remains of the city, but it is more romantic to go up the old Roman road with its bumpy paving stones. At a certain point, the road (which was the decumanus maximus or main road through the city) passes a threshold into the central part of the city and the rough paving stones suddenly give way to large, smooth flagstones. The remains of shops can just about be made out beside the road.

There are panels with detailed (albeit not always easy to understand) descriptions of the various buildings, and a small map is also handed out at the entrance. At the top of the decumanus maximus, the cardo or main cross-road takes off to the left. It leads past the open space of the forum up to a residential quarter where some of the houses still have the remains of rather beautiful marble tiles on their floors. Originally their internal walls were covered in plaster (of which the odd vestige remains) and would have had wall paintings. Some excavations to the right of the forum have uncovered the remains of some of the pre-Roman Etruscan buildings (under cover).

Turning right from the top of the decumanus maximus, you come to an area of shops – probably the bond Street of Roselle. Further up the hill, the remains of a much earlier Etruscan house have been given a plastic roof. There is not much to see, but it excites the archaeologists because it is an extremely early form of what was to become the standard Roman house with an atrium open to the skies and an impluvium (shallow pool) in the middle to collect the rainwater. Beyond this there are the well-preserved remains of the Roman amphitheatre (1st century AD) with walls of opus reticulatum – a well-known Roman building technique of placing square bricks diamond-wise (reticulatum means webbed).

The right hand exit from the amphitheatre leads back to the entrance along a very long path that takes you past the huge Etruscan walls. For a shorter walk, retrace your steps back down to the entrance, near which there are the remains of some Roman baths on the right. These are the only things on the site which can be dated, as an inscribed stone was found indicating that they were opened by Betitius Perpetuus Arzigya, the governor of Tuscia and Umbria from 366-370 AD.

Photo Wikimedia)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SAN GALGANO

San Galgano.pdf version for downloading and printing

A romantic ruined abbey and a chapel with a sword in a stone, well worth a visit.

Open 0800-1200 and 1400 to sunset. About 30 kilometres along the Roccastrada road. Go straight through Rosia and on until you begin to see yellow signs to San Galgano. Visit both the chapel on the hill and the ruined monastery church which lies below it, about half a kilometre away. A vast new paying car-park has just been opened, but most people still park for free in front of the church. Only the disabled are supposed to drive up to the chapel on the hill. There are a couple of snackeries in the grounds.

The legend of San Galgano

San Galgano was a rich, aristocratic young man from nearby Chiusdino, born in 1148. Overcome with spiritual longings, he deserted the gay and frivolous life (albeit with a few battles thrown in for exercise) that he was expected to lead, . He built himself a round wooden hut on top of a small hill called Montesiepe, and became a hermit. To demonstrate to his mother and sister his resolution to shun henceforth frivolity and military activity, he plunged his sword into a cleft in a rock which had appeared in the middle of his hut. There it remained stuck until a few years ago when some youths from a neighbouring village dared each other to remove the sword and managed to break off the hilt. It has now been cemented back in and a glass case constructed around it. The whole thing looks thoroughly bogus, but the experts say that it definitely is a twelfth century sword.

The chapel

San Galgano died in his thirties, but he had already become famous for his holiness. Very shortly after his death, in 1182-5, a circular chapel was built on the site of his hut. This remains, together with the sword. A tiny square baptistery opens out of it, covered in good but rather damaged frescoes by the fourteenth century artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti (who did the frescoes of Good and Bad Government in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena). As of 2016, these are in Siena being restored, but they are due to return in 2017.

Photo Wikimedia

On the far wall of the little baptistery, the Virgin and Child sit in majesty surrounded by saints and angels. At some point Lorenzetti changed his mind about the position of the Virgin’s left hand, and a recent restoration has resulted in a three-handed figure, with both the old and the new positions being revealed. At the Virgin’s feet, Eve rather curiously sprawls, a goatskin over her shoulder with a serpent emerging from it, and a fig in her hand. The symbolism is far from clear, but an inscription on a scroll contrasts Eve, the cause of death, with Mary, mother of God, the cause of Life. To the right of Eve, the figure offering a heart to the Virgin is St Gertrude; and San Galgano is offering something in a straw basket. At the bottom of the fresco there is an Annunciation, where again restoration has revealed changes. Originally, the painter gave the Virgin a rather horrified expression; but this was felt to be inappropriate, and she was repainted with her present serene face.

On the left wall, San Galgano appears in the fresco, carrying a diminutive slice of rock with the sword sticking in it. He is offering the sword to Michael the Archangel as a sign of the consecration of Montesiepe as a holy place, and Michael invites him with a gesture of his arm to regard the Virgin. The two Bishops of Volterra who were responsible for the chapel hover behind the saint. Below, there is a rather fanciful representation of the Castel St Angelo in Rome with an angel on the roof putting a sword away as a sign of forgiveness. On the opposite wall, a large company of saints and angels is walking towards the Virgin.

In a little room at the entrance to the chapel, honeys and strange liqueurs and obscure tisanes with allegedly curative properties are sold. The "millefiori" honey is good.

The abbey church

Later, in 1218, a Cistercian abbey was built below Montesiepe, one of the largest in Italy, modelled on the great Cistercian foundations in Burgundy; indeed in style it is far closer to severe French (or English) Gothic than to the lacier Italian version. St Bernard, who founded the Cistercian order, laid down precise rules on the design of the buildings of his abbeys, with refectory, dormitory and chapter-house all in their allotted places, and these rules have been closely followed. In its hey-day, the monastery was the richest, largest and most powerful in the region, owning all the land around and operating like a little city. Cistercian monks did not stay in their monastery, and monks from San Galgano served as notaries, treasurers, doctors and architects in the Sienese Republic. They also worked the nearby mines. In the fourteenth century, however, the monastery was sacked by the English mercenary captain, Sir John Hawkwood of the White Company, who was employed by both Florence and Pisa at different times to fight their battles. The Black Death followed hard on Hawkwood’s heels, and the monastery never recovered. It went into a long decline; by 1550, there were only five monks left, and 50 years later only one monk in ragged clothes remained. Finally, the monastery became a farm and the abbey was plundered for its stone. Now all that remains are the great walls and windows of the abbey church, romantically roofless but still inspiring, together with two rooms of the former the monastery: the scriptorium (where the monks sat creating their illuminated manuscripts) and the chapter-house, together with a tiny bit of cloister.

The roofless remains of the great abbey church

1980s; revised 2005.

***********************************************

Chiusdino

The entrance ticket to the abbey also entitles the visitor to visit a small new “Museum of San Galgano” in Chuisdino, about 10 kilometres away (turn left on emerging from the San Galgano complex). Chiusdino is a typical fortified hilltop town of extremely steep and narrow streets where parking is difficult, and the museum is of strictly limited interest with signs only in Italian. But for those who do make it to Chiusdino, the museum (which opened only at the beginning of 2016) is up a street to the left of the Palazzo Pubblico. It contains mostly religious objects and pictures gathered in from the local churches. The best things are on the first floor, including a marble bas-relief of San Galgano dated 1466 by Urbano da Cortona (below).

Chiusdino retains an exceptional number of its medieval houses including the house where San Galgano was born – it is signed from the main street and getting to it involves clambering up through a maze of small streets. The house looks suitably ancient but is otherwise of no interest (the ground floor has been turned into a chapel).

San Galgano plunging the sword into the stone

2016

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MASSA MARITTIMA

A beautiful small mediaeval town on the way to the seaside, with one of Italy’s prettiest main squares.

Massa Marittima is divided into an upper and a lower city. The Duomo is in the lower city (città vecchia), which was the original walled town in Romanesque times, but the best museum (Museum of Sacred Art) is in the slightly later upper Gothic city (città nuova). As its name indicates, Massa Marittima (accent on the first i) was once near the coast, overlooking an arm of the sea from its hill-top. But the silting up of the coast changed this and one now has to go another 20 km to Follonica to find the sea.

The hills that Massa stands on are called the Colli Metalliferi or the metal-bearing hills. The city has since Etruscan times been a mining centre, drawing its wealth from copper, silver, lead and iron. The town has a mining museum displaying memories of that past.Turn right off the main square up via Goldoni and then right again. It is underground in an old mine and they will want to make sure that you have adequate footware before letting you in. You have to join a guided tour all in Italian.

The Duomo (Cathedral)

Duomo with the Palazzo del Podestà on the right

The beautiful Duomo was built in the 11th century in the Pisan Romanesque style with Gothic additions in the 13th century. There is some Sienese stripiness in the higher part of the building, but most of the Duomo is built of a lovely uniform golden stone. It has a wonderfully sculpted and decorated façade, and a fine campanile with the number of windows increasing towards the top in the Lombard style.

The Duomo is dedicated to St Cerbone, the local saint. He was born in Africa in 493, but moved to Populonia, a major Etruscan town near what is now Piombino. He became its Bishop and set about converting the Maremma (as the surrounding region is known). He was accused of heresy, however, and papal messengers came from Rome to fetch him to answer the charges against him. He treated the messengers well, feeding them does’ milk, and went with them to Rome, accompanied by a gaggle of pious geese. When he arrived before the Pope, the geese miraculously appeared at his feet as a testament of his innocence. Having successfully refuted the charges against him, he faced another trial, being thrown to the bears by King Totila of the Goths, but the bears refused to eat him. St Cerbone was clearly afraid that he was not going to be so lucky a third time, as when the Lombard invaders arrived in that part of Italy, he promptly withdrew out of their way to Elba, where he died. Scenes from his life are depicted in the low relief above the main door of the Duomo.

Inside, the Duomo is equally attractive, basilica-shaped, with the minimum of vulgar modern intrusions. It is dotted with charming fragments of mainly 14th century frescoes, but its main delights are its sculptures.

Behind the side entrance on the left wall, there is a 3rd century Roman sarcophagus with winged figures in distinctly flirtatious rather than religious mode; note the two couples at either end. On the other side of the side entrance door, the fresco representing the Three Kings is a rather splendid affair. Note the monkey with an almost human head on the left-hand side – the artist may never have seen a monkey .

The chapels on the left of the main altar contain both a fine painted wooden crucifix by the Sienese painter Segna di Bonaventura (1298-1331) and a beautiful if rather damaged and green-faced ‘Virgin of the Graces’, dated 1318, circle of Duccio.

The main altar itself is a fine piece of Baroque (1626) in ‘giallo di Siena’, a yellow marble that is only found near Siena, that fits in surprisingly well with the rest of the church. Behind it is the "Ark" of St Cerbone, sculpted and (unusually) signed and dated by Gori di Gregorio of Siena in 1324. It is decorated with a strip cartoon life of the saint; note especially the does being milked to assuage the thirst of the papal messengers, and the geese first going with the saint to Rome and then materialising around his feet as he confronts the Pope. Unfortunately, the authorities have recently decided that the footfall of tourist looking at the Ark is damaging the ancient pavement and it is currently (2023) roped off.

.

St Cerbone arriving at Rome on the left and before the Pope on the right.

Note the pious geese at the bottom of both scenes.

On the right of the entrance, there is a huge square font made by Girolamo da Como in 1267 with fine sculpted scenes from the Old and New Testaments; on top, an equally handsome but stylistically quite different fifteenth century tabernacle has been added.

The Piazza

The triangular Piazza in which the Duomo stands is one of the most beautiful in Tuscany. It is well worth sitting a while in one of the cafés to soak up its beauty and that of the Duomo, which stands at an oblique angle to the Piazza, rather like a stage set, enabling one to see at the same time the façade and the side wall with the campanile.

To the right of the Duomo, there is the attractive 13th century Palazzo del Podestà, from which the magistrates of the city operated; many have left their crests on the front of the building (which now houses the museum). The museum within it is of little interest, its only good painting having been removed to the Museum of Sacred Art in 2005. Beyond the Palazzo del Podestà, after an attractive small house, stands the 14th century Palazzo Communale, or town hall, a handsome block of a building with crenellations.

The Palazzo Communale seen from the steps of the Duomo.

Fonte dell’Abbondanza and Albero della Fecondità

Just below the Duomo stands one of the most curious monuments in Tuscany, the Fountain of Abundance decorated with a “tree of fertility”, its fruits being erect penises. The building is a standard public water fountain dating from 1265 (the date is on the building) with three Gothic arches and pools inside which the townsfolk used for water and washing. During a restoration of the fountain in 1999, an extraordinary fresco on the back wall was uncovered, depicting a tree with 25 masculine organs hanging from it. Below stand a number of women, two apparently fighting over one of the “fruits” from the tree; another trying to pluck a phallus from the tree (or possibly scare off one of the menacing black birds flying around); and one on the left holding a phallus behind her back.

The fertility tree

It is thought to date from between 1265 and 1335. The experts are divided on its significance. Some see it simply as a fertility symbol, the penises representing abundance. Some experts, however, sees a political significance. It was created during a time of jockeying for position between Guelphs (supporters of the Pope) and Ghibbelines (supporters of the Holy Roman Emperor). When the fountain was built in 1265, the Governor of Massa was a Ghibelline and one interpretation is that the fresco depicts good and bad government under the Ghibbelines. On the left the citizenship is at odds (the scene of women squabbling): everyone is competing for resources that are not sufficient, and the many eagles represent the factions into which the Ghibelline government was divided before the fountain was built (the eagle was the heraldic symbol of the Holy Roman Emperor). On the right, with the creation of the fountain, there are no more problems and people live in peace under a single Ghibelline eagle. Another expert believes that the fresco dates from a few years later when the Guelphs were in control and represents a Guelph political message warning those using the fountain that a return of the Ghibbelines would bring withchcraft and sexual perversion. According to this interpretation, the birds represent hostile imperial eagles and the women are witches (there were contemporary legends of witches who cut off men’s penises).

The building above the fountain was built slightly later and was used as a granary, which is thought to have inspired the name of Palazzo (and Fonte) dell’Abbondanza. Underneath the fountain there is a 265 metre tunnel which can be visted by special arrangement.

The new city (città nuova)

Those who have the energy should now take the steep via Moncini, leading off from the Piazza at the far side from the Duomo, to the higher city (one can also drive up round the outside).

The gateway at the top of the via Moncini is all that is left of the Fortezza dei Senese, the fortress that the Sienese built when they conquered Massa in 1355. The tower on the left as you pass through the gateway is a similar remnant of the fortress built in 1228 by the previous regime, the Fortezza dei Massetani. The Sienese, when they took over, pulled most of it down, rebuilding it to only two-thirds of its original height and constructing a flying bridge across to their own fortress. In good weather, the tower (known as the Torre Candeliere or candlestick tower) is open between 11-13.00 and 17-19.00 daily except Mondays. One can climb up (very steep steps) onto the flying bridge, or higher still onto the belfry on top for a good view of the surrounding countryside. Inside the tower, at the same level as the flying bridge, the works of a clock installed in 1610 can be seen, although they are now non-operational and the clock works by electricity.

Beyond the Torre Candeliere along Cirso Diaz there is a Gothic (mainly 13th century) church, Sant’ Agostino, on the right with a slightly later cloister alongside. Inside the church there is a single nave unusually combined with a triple apse, but otherwise little of interest. Beyond San Agostino is a museum of ancient organs and other keyboard instruments and then the Museum of Sacred Art.

Museo di Arte Sacra (Museum of Sacred Art)

This is a new museum, only opened in 2005. It is beautifully laid out and well labelled, including in English. It is at 36 Corso Diaz, opposite the hotel La Fenice, at the far end of the new city. Opening hours are 10.00-13.00 and 15.00-18.00 daily except Mondays (11.00-13.00 and 15.00-17.00 in winter).

The first room has some rather fascinating bas-reliefs that used to be in the Duomo. They are extremely archaic in style, and debate rages among the experts as to whether they are genuine pre-Romanesque works from the 10th century or some later medieval fantasy (the description in the museum ascribes them to the 12th century). There is inter alia a very modern bishop with crosier and mitre who might be St Cerbone; a row of the twelve Apostles (note St Peter with his key on the right); and a stylised but moving representation of the Massacre of the Innocents with Herod looking like a playing-card king, two soldiers chopping off heads of infants and mothers clutching their children to their skirts.

Massacre of the Innocents

The second room contains some good 14th century statues of apostles with magnificent beards; a 14th century statue of a red-faced bishop who again might be St Cerbone; a wooden crucifix; and an exquisite 14th century silver and enamel crucifix, the last two possibly by members of the Pisano family.

The third room has by far the best picture in the collection, and one of the masterpieces of Sienese art: a Maiestà by Ambrogio di Lorenzetti, dating from around 1330, a wonderfully colourful scene of the Virgin surrounded by angels and saints – including an angel offering flowers at head level and musician angels at the bottom of the Virgin’s throne. The Mother and Child are looking at each other with a close and charming intimacy, faces almost touching. An interesting feature is the way that the angels’ wings make up the sides of the throne. On the steps at the base of the throne, figures are seated representing Faith, Hope and Charity, the last clearly the same lady as Justice in Lorenzetti’s ‘Good and Bad Government’ in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. Hope on the left in a dark robe holds a tower; there are debates over the symbolism, but it could represent ascension towards the divine, or else the edifice of the Church. Flame-coloured Charity in the middle, with open arms, holds an arrow and a heart, symbols of divine love. Faith in white at the bottom of the throne holds what is said to be a representation of the Trinity – there was apparently once a dove above the two faces.

The painting was intended for the Duomo, and St Cerbone and his geese are portrayed on the right. At some point the painting was removed from the Duomo, and it was lost for ages, finally to be found in pieces in the roof of a nearby convent in 1867, so it must have been fairly heavily restored.

Musical angels and at the base of the Virgin’s throne, together with Faith, Hope and Charity.

Note the geese at bottom right.

There are two rooms upstairs. The first has a motley collection of sculpture, paintings and pottery, of which only the painting on the end wall is worth more than a moment’s glance: it is a stable scene by Pietro degli Oriolo (1458-96), one of the better of the later Sienese painters. The stable is the attractively crumbling romantic ruin that had succeeded the gilded Gothic pavilion as the standard way of depicting Jesus’s birth-place. St Bernardino is portrayed on the left with his trademark thin face, and on the right some shepherds peep shyly over the stable wall. The final room has some dimly lit old vestments and illuminated manuscripts.

On to the seaside

From Massa it is an easy drive to Follonica on the coast. There are beaches to the North and South of the town. Those to the South, which stretch for several miles along the road towards Punta Ala, are sandy and shallow and good for children but not serious swimmers. There is a narrow band of pinewood between the road and the beach; it is usually possible to park by an entrance to the pinewood and walk through.

(1999, 2005, 2016, 2023).

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

COMMUNE OF SOVICILLE

The small town or large village of Sovicille, which gives its name to the commune (Council district) in which Barontoli lies, is of pretty limited interest. However, there are a number of places nearby that are worth visiting if one is staying in the neighbourhood, the cloister at Torri being the star.

*************************************************************************

Ancaiano

This little village near Sovicille is of limited interest, but the church of San Bartolomeo may merit a brief glance if you are passing by. The interior is closed.

Rear view of San Bartolomeo in Ancaiano.

Originally, as in so many of the local villages, there was a church was built in mediaeval times. In 1554, however, when the troops of the Holy Roman Emperor were marching towards Siena to join forces with their Florentine allies in order to subjugate Siena, they managed to cause such damage to the church that it had be completely rebuilt.

The present building dates from 1660 and is Renaissance in style. Built on the instructions of Pope Alexander VII (whose Chigi family originated in Siena), it is said to be based on designs by Baldassare Peruzzi, one of the great Italian architects of the age, who usually designed much grander things but probably took the commission because he was born in Ancaiano.

The church is set among trees and was deliberately built a little way from the road so that all sides could be admired, a desired characteristic in Renaissance times. The rear of the church can be seen beyond a garden on the road into Ancaiano from Sovicille; the entrance to the church with its handsome classical façade is accessible via a side road. The interior is apparently in a bad state and in 2019 there was an angry notice stuck on the entrance door castigating both the Church and local government authorities for not doing anything to save it.

2019

Cetinale

A very impressive villa, unfortunately hard to see.

To reach Cetinale from Sovicille, take the road to Ancaiano, and at the entrance to the village turn right along the unpaved road sign-posted Cetinale.