| |

CITY OF SIENA

MUSEUMS AND SECULAR BUILDINGS

|

Streets and the Campo - a brief description of the main streets and grand houses.

Palazzo Pubblico - dominating the Campo (Siena’s main square), it is one of the great secular buildings of Italy.

Palazzo del Governatore dei Medici - the headquarters of the Medici when they ruled Siena, next to the Duomo (interior not normally open to vistors).

Other Palazzi

Cathedral Museum (Museo del OPA) - another of the musts of Siena. It contains Duccio’s masterpiece, the Maestà, and a number of other important works, and also gives access to the top of the Facciatone, the intended façade of the new cathedral which was never built, from which there are great views.

Hospital Santa Maria della Scala - Siena's ancient hospital, now a museum. It contains one of the best non-religious cycles of frescoes in Italy, and now houses the Etruscan collection of Siena and various other collections.

House and Sanctuary of St Catherine - St Catherine family home, now a sort of shrine.

Pinacoteca - Siena's main picture gallery. It contains almost only Sienese painting, but of that it has the finest collection in the world.

Siena State Archives - A little visited but fascinating display of painted file covers (“Biccherne”) from Siena’s 13th-17th city account books.

Oratorio San Bernadino - One of the most delightful galleries in Siena, small enough to avoid cultural indigestion and containing a perfect frescoed room and a masterwork of Sienese painting. Despite this, it is very little visited.

The Fountains of Siena - The fountains that supplied Siena with water in times past.

The Gates of Siena

Porta Camollia

Porta Pispini

Porta Romana

Porta San Marco

Porta San Maurizio

Arco alle Due Porte

Arco dei Frati Minori or di San Francesco

***************************************************************

Note that there is a particularly idiotic ticketing system for Siena museums, reflecting the centuries-old rivalry between the ecclesiastical and city authorities. Those establishments under the control of the Church (the Duomo and its various parts, the museum of the OPA and the Oratorio San Bernardino) now have a centralised ticketing system based in an office next to the Duomo. The museums under city control usually have their own ticket offices on site, but tickets both the Hospital Museum and the Pinacoteca now (2023) have to be purchased in the tourist office near the front of the Duomo. Both sets of authorities have various arrangements for combined tickets. Fortunately, it is now fairly easy to book online.

Some palaces (palazzi) and churches with interesting interiors are included in this guide, even though they are normally closed, just in case you should hap upon a day when they are open, for instance when they are being used for a concert or special exhibition.

***************************************************************************

MAIN STREETS AND THE CAMPO

The via Francigena and the road layout

In the Middle Ages, Siena owed much of its trade to the fact that it was not only on one of the main roads from Florence to Rome, but was also on the ancient pilgrim route known as the Via Francigena, “the road that comes from France”. This was the route that pilgrims took from Northern Europe to Rome and Jerusalem. Its northernmost point was in fact Canterbury, and one of the people known to have used the route to go to Rome was Sigeric the Serious, a 10th century Archbishop of Canterbury. His journey took some 80 days, travelling about 20 kilometres a day. The route went through France, Switzerland and Italy. Sigeric’s journey took him through San Gimignano; Badia a Isola; Siena; Ponte d’Arbia; and San Quirico d’Orcia.

To this day, the backbone of Siena is the main street that starts in the North at the Porta Camollia (the ancient gateway into Siena from Florence), where it is called via Camollia; after that it becomes first via Montanini and then Banchi di Sopra. It leads down to the Piazza del Campo (normally known simply as "The Campo"), the beautiful main square, where it splits into two. The left hand fork, Banchi di Sotto goes on down to the Porta Romana, the gateway to the ancient main road to Rome. This is the way that travellers from Florence to Rome and pilgrims on the Via Francigena took in ancient times. The right hand fork, via di Città, leads out to the Porta San Marco and the road towards the south-west.

Looking down via di Città towards the three-way junction or “Travaglio” – Rome to the right, Florence to the left. The marble arcaded building just visible on the right is the 15th century Loggia della Mercanza, which in olden times housed an internationally respected commercial court.

The Campo

The sloping scallop-shell-shaped Campo, where the Palio is run twice a year, is one of the most famous squares in Italy if not the world. The Town Hall or Palazzo Pubblico straddles the lower side, and ten lines of travertine marble radiate out from in front of it, dividing the Campo into nine segments, said the represent "The Nine" (I Noveschi), the medieval government of nine magnates who laid out the Campo in its present form in 1349. The great medieval families of Siena built their palazzi round the hemi-circle of the scallop shell. Most have been much changed over the centuries, and now all have cafés, restaurants or shops at their base. The cafés and restaurants are expensive (and the restaurants not partticularly good), but well worth it for the view over this fabulous square.

Painting of the procession of the Contrade around the Campo in 1546. Note that several of the

palazzi still have their towers.

As can be expected, many of the best palazzi are on the Campo.

- Palazzo Sansedoni is the most impressive of the palazzi on the Campo. It was built in the 1300s, but reconstructed in 1767, so its medieval look is probably too good to be true. But it is still a fantastic building.

Palazzo Sansedoni in the centre; Palazzo Chigi-Zondadari on the right.

- Palazzo Chigi-Zondadari, to the right of the Palazzo Sansedoni, is probably the most recently built, being a graceful 18th century building, nevertheless fitting well with its medieval or pseudo-medieval neighbours. It was built by a Roman architect for a Sienese cardinal called Zondadari, demonstrating the being a cardinal was still a good guarantee of riches in those days.

- Palazzo Pannochieschi d'Elci or degli Alessi, the tall crenellated building on the other side of the Campo, was first erected in the 1200s by the Alessi family; but was then taken over by the Pannochiesci d'Elci family and remodeled in the 1500s. It was remodelled twice more over the centuries, so it is hard to tell how much of its medieval appearance is genuine. But again it is a fine building and the café at its foot is a good place in which to sit and admire the Campo..

Palazzo degli Alessi in the centre with the crenellations

2012 and 2014.

Minor changes 2014.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

PALAZZO PUBLICO – SIENA TOWN HALL

Dominating the Campo (Siena’s main square), it is one of the great secular buildings of Italy, with Simone Martini’s masterpiece, the Maiestà, and the iconic fresco of the horseman Guidoriccio da Fogliano riding through the Sienese landscape. A must.

The building still functions as the town hall, and only part of the first floor, the Museo Civico, is open to the public. Entrance from the courtyard to the right of the little loggia at the bottom of the tower. Open evey day 10.00-19.00 (summer) and 10.00-17.30 (winter). Separate ticket to go up the tower (Torre Mangia).

A huge, austere but graceful Gothic structure with magnificent crenellations and a tower that can be seen for miles around, built in the early 14th century when Siena was riding at her highest, just before the disaster of the Black Death that carried off half her population. The stone loggia below the tower, the Cappella di Piazza, was built later, in 1376, in thanks for the end of the Black Death, and later altered to assume its present Renaissance appearance. The tower is 97 metres high and needless to say the views from it are fantastic, but first 388 steps need to be climbed. Commonly known as La Mangia, it is said to take its name from its first watchman, who was a spendthrift or “mangiaguadagni” (wage-eater). The right-hand side of the building still functions as a town hall and is full of municipal offices.

Sala di Risorgimento

Two flights of steps lead up to the left-hand part, open as a museum. At the top, turn left straight into the Sala del Risorgimento (rather than right into some rooms with a rather boring selection of depressingly brown paintings). This room was frescoed in the late 19th century to commemorate various episodes the life of Vittorio Emmanuele II of Savoy, the first king of a united Italy. The frescoes form a fascinating modern take on the typical narrative frescoes of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Vittore Emmanuele was severely height-challenged, explaining why he was so often represented on horseback or standing apart from anybody who would tower over him. The cycle starts at the left end of the entrance wall and goes from left to right:

- Encounter at Vignole in 1849, when Vittorio Emmanuele met the Austrian Marshall Radetsky who had just defeated his father. The latter had abdicated, leaving his son, as the new king of Savoy, to conclude a ceasefire.

- Battle of Palestro, in 1859, when the Austrian forces were defeated by Vittorio Emmanuele’s Piedmontese forces.

- Battle of San Martino (better known as the Battle of Solferino) in Lombardy in 1859, when French forces under Napoleon III and Italian forces under Vittorio Emmanuele decisively defeated the Austrian army led by Emperor Franz Joseph I. It was the last major battle in Europe where the sovereigns personally commanded their forces.

- Meeting at Teano between Vittore Emmanuele and Garibaldi in 1861 (picture below). Vittorio Emmanuele had just been declared king of a united Italy and received from Garibaldi the control of Southern Italy.

- Funeral of Vittore Emmanuele in 1878. One of the figures in the second row of the cortège is Lord Clarendon, representing Queen Victoria.

Sala di Balia

The next room, the Sala di Balia, has a 15th century cycle of frescoes by Spinello Aretino (c.1350-c.1410), portraying scenes from the life of the Sienese Pope Alexander III (pope from 1159 to 1181), chiefly known in England as the pope who humbled Henry II over the murder of Thomas à Becket.

Alexander’s election as pope was disputed, with some cardinals claiming to have elected a rival candidate supported by the great German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. In 1176, however, Barbarossa was defeated by the Lombard League at the battle of Legnano and subsequently recognised Alexander as pope. A spirited depiction of the battle is shown above one of the doors, and Alexander’s triumphant return to Rome (which he had been forced to leave) is above the other door. There are other scenes from Alexander’s life on the inner wall of the room.

The Emperor humbling himself before the Pope

Anticamera del Concistoro

The Anticamera del Concistoro follows and has been used to display various bits of detached fresco from elsewhere. The best is the one above the door with saints and the donor who no doubt paid for it (as always miniaturised compared to the saints), attributed to Ambrogio Lorenzetti and originally part of a much larger work. There is also a St Sebastian stuck with a truly excessive number of arrows.

Sala del Concistoro

Beyond is the Sala del Concistoro, which is still used for civic marriages (hence the chairs), and is sometimes closed because a marriage is taking place (an increasing number of foreigners come to be married in this magnificent room, for which the City of Siena now charges a handsome fee). The frescoes in the vault are by Siena’s mannerist master, Domenico Beccafumi, portraying various civically uplifting scenes and personages from ancient Greece and Rome. Note also the very beautiful carved marble doorway dating from 1448.

Sala del Consistoro, still used for weddings

The Mayor relaxing between weddings on a Saturday

Vestibolo and Antecappella

Back to the Anticamera and through a side door, you come to the Vestibolo and Antecappella, with a huge fresco of St Christopher above the door by Taddeo di Bartolo (c.1362-1422). To the left is the Cappella (Chapel), also frescoed by Taddeo di Bartolo with scenes from the life of the Virgin. Above the altar there is a particularly beautiful Virgin and Child by Sodoma (1477-1549). Note also the inlaid choir stalls and the wrought iron screen attributed to Jacopo della Quercia (1374-1478), Siena’s greatest sculptor.

Sala del Mappamondo

Now for what is possibly Siena’s biggest treat, the vast Sala del Mappamondo, with at one end Simone Martini’s Maestà and at the other the equestrian portrait of Guidoriccio da Fogliano that is probably Siena’ s most reproduced painting.

The Maestà was painted in 1315, only a few years after Duccio had finished his Maestà for the Duomo (now in the Museo dell’ OPA). Both represent almost exactly the same personages. The Virgin is enthroned in the centre with the Christchild; and the four patron saints of Siena (Ansano, Savino, Crescenzio and Vittore) are kneeling in the front row. Behind them is the same host of angels interspersed with a scattering of the usual saints (the saints don’t have wings). St Paul with his usual black beard and sword is on the extreme left; next to him is the Archangel Gabriel with St Mary Magdalene in red slightly behind and then the grey-bearded St John the Evangelist and St Ursula. On the other side of the Virgin St Catherine of Alexandria stands next to a particularly wild-eyed and wild-haired St John the Baptist; then slightly behind St Agnes with her symbol of a lamb; the Archangel Michael, and St Peter holding a huge key. More lesser saints are behind them.

The iconography may be the same as in Duccio’s Maestà , but in spirit Simone Martini’s version is wholly different. The fact that it is a fresco gives it a lightness and delicacy not attainable by paint on panel. That is not all, however. The figures are still static, but are much less stiff and portend the sinuousness of the “international Gothic” movement of which Simone Martini (c.1284-1344) was to become a leading exponent. Simone Martini has also given the scene a sense of place and space, and even the beginnings of perspective, by the introduction of a baldacchino or canopy over the whole assembly, held aloft by apostles.

At the other end of the room, high on the wall, the richly dressed horseman Guidoriccio da Fogliano, Captain of the Sienese Army, rides out to lead his troops into battle, across a typical southern Sienese landscape, with its bare grey clay hills. It is an extraordinarily attractive work and has always been considered to be another masterpiece by Simone Martini, painted in 1328, extremely unusual for the period in portraying a completely unreligious theme. In 1977, to the fury of the Sienese, an American art historian, Gordan Moran, had the temerity to suggest that it was just a bit too unusual (and the architectural style of the towns in the background inconsistent with the period), and that the work was in fact painted many years later by a quite different artist. The debate among art historians is still raging fiercely, but nothing detracts from the beauty of this fabulous work.

There have always been arguments about the attribution of the fresco below Guidoriccio, showing the handing over of a fortified village to a representative of the Sienese republic. Some claim it is by Duccio. The circular space may have been the site of a great circular (and possibly revolving) map of the Sienese Republic’s territory, painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, the mappamondo that gave this room its name. On either side are two of Siena’s patron saints, St Victor and St Ansanus, by Sodoma in 1529. On the long wall opposite the windows there are further saints. Above, there are two spirited 15th century battle scenes, both needless to say representing Sienese victories.

Sala del Pace

The next room, the Sala della Pace, contains some of the most interesting frescoes in the whole of Italy, fascinating in their detail of medieval life. They were painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c.1290-1348) in 1338 and represent an allegory of Good and Bad Government. Good Government is on the entrance wall. It portrays a bustling city with shop-keepers, a magistrate in his courtroom, a roof being repaired, citizens going peacefully about their business, peasants coming into the city with their wars and hunters riding out, and a neatly cultivated countryside with vines and fields of corn. On the other side of the room, unfortunately badly damaged, Bad Government has resulted in a city of houses falling into ruin, fights in the street and citizens bearing arms, no visible economic activity and an uncultivated countryside.

|

|

Good Government – see Siena Cathedral

top left |

Bad Government with broken buildings |

On the end wall Ambrogio has painted a complicated Allegory of Good Government. The symbolism of much of it remains obscure. But the doninant figure on a throne, with a robe in the black and white colours of Siena, is clearly some sort of Guardian or representative of the common good. At his feet, the baby Remus (father of Senius, the legendary founder of Siena) and his twin brother Romulus are suckling their adoptive wolf-mother, who is tenderly licking one of the babies. Figures representing Faith, Hope and Charity hover above the Guardian.

The seated figure on the left represents Justice, above whom hovers Divine Wisdom, holding the traditional scales in one hand and a book in the other. In the plates of the scales, two angels sit. The one on the left, representing the Aristotelian concept of “distributive” justice, is about to decapitate one person while at the same time placing a crown on the head of another. The angel on the right, representing “commutative” justice, is handing some merchants the equipment they will need for measuring out their goods.

The next bit of symbolism is particularly difficult to understand. From the scales two threads descend into the hand of Concord, who is holding a plane on her lap, symbol of levelling or equality. The threads continue on in the form of a rope held, tug-of-war-fashion, by a group of 24 citizens, representing presumably the community of Siena. Experts still argue about what exactly this all means, but one suggestion is that the rope is holding the citizens together in harmony.

Above the citizens yet more virtues are seated comfortably on a sofa covered in a rich cloth – Peace lounging comfortably, in a white robe. Below them, the city’s armed forces guard some prisoners. Fortitude and Prudence. Magnanimity, Temperance (with an hour-glass) and Justice (this time with a sword) sit on the other side of the Guardian.

Peace (with an olive branch), Fortitude and Prudence.

The next room is something of an anti-climax, with some bits and pieces that one can afford to miss. Going back towards the Sala del Risorgimento, there is a stairway up to a balcony with the usual good views.

2012.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PALAZZO del GOVERNATORE dei MEDICI (Palace of the Governor of the Medicis) or Palazzo Reale; now the Prefecture and seat of the Provincial Council

On one side of the Duomo. The second biggest palazzo after the Palazzo Pubblico. Only occasionally open to the public.

This large palazzo, also sometimes known as the Palazzo Reale (Royal Palace), is on the right side of the Duomo and is the second biggest palace in Siena after the Palazzo Pubblico on the Campo. It occupies the whole block between the unfinished nave of the new cathedral and via del Capitano, on the right side of the Duomo.

After the Florentine takeover of Siena in the 1550s, the ruling Medici family made it their headquarters in Siena – perhaps not quite daring to move into the Palazzo Pubblico with its weight of history. It is now the Prefecture or office of the provincial administration of Siena and the home of the provincial Council. It is rarely open to the public (unless on business), but many of those who work there benefit from rooms hung with tapestries and with frescoed ceilings.

Ancient and modern: office of the President of the Provincial Council

The palazzo was built in the late 1400s by the brother of Pandolfo Petrucci, the then dictator of Siena. In 1593 the Petrucci family sold the palazzo to the Medici. They completely remodelled it over the next couple of years, with further modelling of the façade in the via del Capitano in 1629 by Prince Mattia dei Medici, the then Governor of Siena. When the Medici first acquired the palazzo, the Bishop’s palace stood on the now empty space between it and the Duomo. The Medici also acquired this palace and had it demolished so that their Governor or members of the family staying there could have a view of the Duomo from their windows.

It is a classical renaissance building with a fine porch in the centre of the main façade. The flags of Italy, the EU and the Province of Siena (whose crest is a lion with a crown and oak and olive leaves) normally hang above the entrance. The main façade is stucco, but the handsome internal courtyard is partly in typical Sienese red brick. The main rooms are on the first floor and are hung with 16th century tapestries depicting scenes from the life of Cosimo dei Medici the Elder (1389-1464), the first member of the Medici banking family to acquire major political power in Florence; hunting scenes; and stories from mythology and the Bible. Some of the tapestries were made in Flanders, one of the great tapestry manufacturing centres of the period. But the Florentines then set up their own manufacture and many come from there. The Florentine tapestries are notably cruder, although with their own robust charm.

The magnificent Audience Chamber of the Medicis is now the provincial Council Chamber (Sala del Consiglio) with benches and microphones. Alone of the rooms on this floor it retains its original coffered ceiling (almost all the others have been redone in stucco with 1830s frescoes by Cesare and Alessandro Maffei). The President of the Council has his office in the “Room of Justice” (Sala delle Giustizia) after the ceiling fresco.

Ceiling fresco of Justice

Next door, the “Room of the Meeting” (Sala dell’Incontro), retains its beautiful 16th century silk wall covering. The room is so called after the ceiling fresco which represents Pia de’ Tolomei meeting her husband Nello Pannocchieschi, Lord of Castel di Pietro in the Maremma. She was, according to legend, an Italian noblewoman (the Tolomei were one of Siena’s leading families) who was supposedly murdered by her husband in the late 1200s either because he suspected her of having an affair, or to marry someone else (there are various versions of her story and she is mentioned in Dante’s Divine Comedy).

16th century silk wall covering

There are further frescoes in lunettes showing episodes of Pia’s life in the “Room of Pia” (Sala della Pia), following a version of the tale in an 1822 poem by Bartolomeo Sestini. If you do manage to penetrate the Palazzo, the series begins on the wall opposite the entrance, on the right and then goes round clockwise. The first scene shows Nello (who has been sent a secret message by his cousin the wicked Ghino claiming that Pia has been unfaithful) mistaking Pia’s brother for her lover.

On the wall to the right are scenes showing:

- Nello arranging to depart for his castle in the Maremma with the secret intention of imprisoning Pia there;

- The couple riding towards the castle;

- Nello giving orders to the guardian of the castle, presumably about imprisoning Pia;.

On the next wall (opposite the window), the scenes show:

- Nello leaving his wife, believing her to be unfaithful;

- Pia despairing at finding she has been imprisoned in the castle;

- A hermit near the castle;

On the wall to the left of the window, scenes show:

- The hermit meeting Nello by chance and telling him a story that hides the truth;

- The hermit and Nello meeting the dying Ghino who reveals that he had calumnied Pia after having tried to make love to her and been rebuffed;

- Nello realising his mistake and wanting to go quickly to the castle.

Back on the window wall scenes show:

- Nello getting on a horse, encouraged by the hermit;

- Nello arriving too late and finding his wife dead and about to be buried.

Finally, the fresco on the ceiling shows Nello being consoled by a sad Pia.

The Palazzo contains a number of paintings, none of major interest. In one of the ante-chambers, there is a striking 17th century portrait of members of the royal family of Savoy (who were much later to become the kings of Italy) by an unknown artist. There is also a portrait of Prince Mattias dei Medici as a young man.

For a (not very good quality) “virtual visit” of the interior, see:

http://visitapalazzo.provincia.siena.it/pages/visitavirtuale.html

2020

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Other Palazzi

The main streets through which the pilgrims and travellers passed are lined with the medieval palazzi of the powerful families of Siena (many of which would originally have had towers); and they are also the main shopping streets. The palazzi include:

- Palazzo Salimbeni, on the Piazza Salimbeni off the Banchi di Sopra. Its white marble Gothic façade is one of the most reproduced images of Siena, but in fact much of it is the result of some heavy remodelling in the 19th century. It was the ancient home of the Salimbeni family and is now the headquarters of Siena’s ancient bank, the Monte dei Paschi di Siena. It was established in the 15th century, is the oldest continuously operating bank in the world and is still a dominant force in Sienese affairs, contributing major subsidies to charitable and artistic activities (although it has had to make major cuts in its activities following the fimancial crisis, when it had to be rescued by the Italian government). It was originally established as a state-run “Monte di Pietà” – a medieval credit institution for lending to the poor. The word “Paschi” was added in the 16th century and comes from an old word for “pasture lands”, as part of the finance for the bank was provided by bonds based on the revenues of pasture lands in the Maremma, south of Siena. The Bank (which has quite a good art collection) does organised tours of the building, but they are not easy to arrange.

Palazzo Salimbeni

- Palazzo Tolomei, further down the Banchi di Sopra on the other side facing Piazza Tolomei. One of the oldest buildings in Siena, it was built in the mid-1200s and is a good example of a gothic private residence. The Tolomei were rivals of the Salimbeni, and it is perhaps fitting the Palazzo Tolomei now houses the Sienese headquarters of the Florentine bank that is the Monte dei Paschi’s main rival.

Palazzo Tolomei

- Palazzo delle Papesse at 126 via di Città. This massive palazzo was built in 1485 for the sister of the Piccolomini pope Pius II, and designed by the Florentine Bernardo Rossellini, the architect of Pienza. It is very much in the Florentine renaissance style, reminiscent of the Palazzo Pitti with its great rusticated blocks of stone. The palazzo was opened in the late 1990s as a gallery of contemporary art, but has now closed again. The collections formerly in it have been moved to the museum complex at Santa Maria della Scala opposite the Duomo.

- Palazzo Chigi-Saracini at 82 via di Città, a gothic-style structure with a lovely courtyard. The nucleus of the building dates back to the 1100s when it the castle of the then powerful Marescotti family. Before the Palazzo Pubblico was built, it briefly housed part of the Sienese government. Only the tower now remains of that early building. The structure changed hands between various dominant Sienese families over the centuries and was enlarged and modernised by them to create the present building. The next door buildings were incorporated into the structure in the 1300s by the Marescotti. In the 1500s when the palazzo was acquired by the Piccolomini-Mandoli family, the renaissance-style inner courtyard was created. In the 18th century the palace was acquired by the Saracini family who lengthened and largely rebuilt the front of the building in 13th century style to create the curving façade of today.

From the Saracini family the palazzo passed by inheritance to a branch of the huge Chigi family, who added Saracini to their name. A 19th century Chigi-Saracini filled the palazzo with works of art and redid much of the interior in renaissance style. The early 20th century owner, Guido Chigi-Saracini, whose passion was music, turned the ballroom into a magnificent concert hall decorated in the baroque style and filled the Palazzo with music and musical mementos. In 1932, with the help of the Monte dei Pasqui bank, he founded a musical academy in the palazzo, the Accademia Musicale Chigiana, which quickly attracted many world famous musicans. The Academy is still operating today as a summer music school and there is a good series of classical concerts during the summer months.

There are guided tours of the palazzo (in Italian and English), which last about an hour. Many of the rooms are closed for music lessons during the summer season, so a visit is more rewarding between September and June. Much of the art consists of huge canvases by Siena’s less distinguished 17th century painters, but there is a good Beccafumi of the mystic marriage of St Catherine in the “piano room”, some interesting pieces of furniture and ancient musical instruments and of course the magnificent if somewhat bogus décor of the rooms.

Courtyard of the Palazzo Chigi-Saracini

THE CATHEDRAL MUSEUM (MUSEO DELL'OPERA METROPOLITANA, OR MUSEO DELL'OPA)

Another of the musts of Siena. It contains Duccio’s masterpiece, the Maestà, and a number of other important works, and also gives access to the top of the Facciatone, the intended façade of the new cathedral which was never built, from which there are great views.

Beside the Duomo. Open 10.00-19.00 daily. A combined ticket can be purchased giving access to the OPA Museum, the Duomo and its crypt, the Baptistery and the Oratorio San Bernardino.

Note: this is not a detailed description of all the objects in the museum, but a summary of the items likely to be of most interest to the casual visitor. As Sienese museums are constantly being rearranged, some objects may no longer be where the notes say they are. Unfortunately, the signing is abysmal.

Entrance to the OPA museum on the left, under the arches of the side aisle of the new

cathedral that was not completed because of the Black Death. The big arch on the right

is the Facciatone, the intended main entrance to the new cathedral.

Ground floor: the sculpture gallery

Immediately after the ticket office there is a sculpture gallery (Room 10). To the left of the steps leading down into it are four rather beautiful early stone panels (late 13th century) of the Annunciation, Nativity, Flight into Egypt and Epiphany, taken from a church not far from Barontoli; and just beyond them on the next wall a frieze from a Roman sarcophagus – the only object remaining from the site of the Roman camp on which the Duomo was built. Donatello’s tondo of the Virgin and Child from above the side door of the Duomo (where it has been replaced by a copy) is at the back of the steps; and on the wall to the left of it there is a beautiful marble panel (1438) by Jacopo della Quercia, the last work of Siena’s most famous sculptor. It shows the Madonna and Child together with Cardinal Antonio Casini (who commissioned the work) being presented to the Madonna by St Anthony Abbot, looking anxious as if fearing that the Cardinal is not quite holy enough.

Jacopo della Quercia sculpture

At the far end of the room, the great rose window designed by Duccio from above the altar of the Duomo has recently been erected, with a light behind it, making it far easier to see than it ever was when in the Duomo (where it has been replaced by a pallid copy). It dates from 1288 and is the earliest major piece of Italian stained glass to survive. Some of its motifs were later developed by Duccio for his Maiestà upstairs, which was painted some 20 years later. Although to our eyes it is rather stiff and Byzantine in style, it is marvellously colourful. There is a particularly effective scene at the bottom of the death (or rather “Dormition”) of the Virgin with crowds clustering round her bed.

The rest of the room is dominated by statues of prophets and philosophers originally made for the façade of the Duomo, rather weather-worn but still with some good faces and poses. The heads tend to jut uncomfortably forward; this is because they were originally high up on the façade and intended to be seen from below. They are by Giovanni Pisano (1245-1318), the son of the man who sculpted the pulpit in the Duomo. Note Moses on the left with rays of light protruding from his head. This is a traditional way of portraying Moses, whose face (according to Exodus chapter 34) shone so much when he came down from Mount Sinai that the Children of Israel were afraid to go near him. Sometimes, owing to an early mistranslation of the relevant passage, the rays are shown as horns, giving Moses a devilish air.

A neighbouring room houses yet more battered statues by Pisano originally made for the Duomo, this time of the apostles. For some reason they were removed and placed in store at the turn of the 17th/18th centuries and replaced by copies by a sculptor called Mazzuoli. These in their turn were sold in 1890 to the Brompton Oratory in London, where they still are. At the end of this room there is the original of the group of Christ as the enthroned Redeemer that was made in 1345 for the great side door for the nave of the projected new cathedral (see final paragraph below). It is in the sinuous “international Gothic” style that within the space of some 50 years transformed the stiff and stylistic art of the period.

First floor: Duccio's Maiestà

This is the glory of the museum and one of the glories of Siena. A “maestà” is a picture that shows the Virgin “in majesty” surrounded by angels and saints. This sort of heavenly court is very much a Sienese invention. There is another big Maestà by Simone Martini in the Palazzo Pubblico, and one in the museum in San Gimignano by Lippo Memmi. But none bears comparison with Duccio’s, the earliest and the inspiration for the others. A work of magical serenity, it was painted in 1308-11 for the main altar of the Duomo, Duccio being the most famous and fashionable artist of the period. When it was completed, it was carried in procession from Duccio’s workshop to the Duomo accompanied by music and most of the population of Siena. There it stayed until 1506 when mediaeval work of this sort became unfashionable. It was removed from the high altar, cut into sections and relegated to side chapels and ultimately to the museum.

The work consists of the main panel plus some 50-odd smaller panels. Those on the side wall were originally displayed above and below the main picture, and the ones on the wall facing the main panel were on the back, to be admired by people walking behind the altar. Not all the panels are here; when the painting was removed from the main altar, some were sold (three are in the National Gallery in London and nine in other museums) and some simply disappeared. Reproductions of some of missing ones have been put up among the real ones.

The main panel shows the Madonna and Child on a sumptuously inlaid throne with a cloth of gold laid over it. At the base of the throne a Latin inscription reads “Holy Mother of God, bring peace to Siena and life to Duccio, because he painted you thus”. Kneeling in the front row of the painting are the then four patron saints of Siena: Ansano, Savino, Crescenzio and Vittore. Behind them on the left are St Catherine of Alexandria; St Paul (as so often with a long black beard); St John the Evangelist carrying his symbol, a book; and then a couple of angels. On the right, after the angels are St John the Baptist, as usual wearing skins and with unkempt hair from his time in the desert; St Peter, for once holding a book rather than a key; and St Agnes carrying her symbol, a lamb. At the very top of the picture the other apostles are portrayed. All the other figures can be recognized as angels from their wings. The painting used to have a carved Gothic frame, with pinnacles and arches, and the marks of where this once was can still be seen.

The greenish hue of the flesh is not deliberate; the pink pigment used at the time was painted over a green ground to give a pale and delicate hue, and unfortunately the fading of the pink with time has led to the current corpse-like colour.

The main panel is a set-piece, carefully arranged according to certain conventions, rather like the final scene of a children’s nativity play. But in the small panels Duccio could afford to adopt a more lively and animated style, and they are well worth looking at in detail. The ones on the far wall represent the Passion of Christ and are set out in strip cartoon fashion, starting in the bottom left corner and going up and down in a zig-zag. The scenes are as follows:

- Entry into Jerusalem (bottom left)

- The washing of the feet (next to it at the top); and the Last Supper (immediately below);

- Christ'sfarewell to his apostles (immediately to the right); and Judas taking the bribe for

betraying Christ (above);

- The kiss of Judas (above); and the agony in the garden (below);

- Peter denying that he had anything to do with Christ; and Christ before Annas the junior

high priest (above);

- Christ accused by the Pharisees; and Christ before Caiaphas the senior high priest;

- Christ in the praetorium; and Christ before Pilate (last two panels on the bottom right).

Go now to the top left:

- Christ again before Pilate (above), and (below) before Herod;

- The crown of thorns (below); and the flagellation;

- Christ on the way to Calvary, and Pilate washing his hands;

- The Crucifixion;

- The deposition from the cross, and the entombment;

- The Marys at the sepulchre (above) and the descent into hell (note Christ standing firmly

on the devil);

- The appearance at Emmaus and "Noli me tangere".

The small panels on the other wall are mostly scenes from the life of the Virgin.

Also in this room there is a delightful early painting by Duccio of the Madonna and Child, fortunately with the flesh still fairly pink. This was painted about 1283, so a good 20 years before the Maestà. Note how the Child is tweaking the Virgin’s veil. Further along the same wall there is a Birth of the Virgin by Pietro Lorenzetti, a Sienese master of the generation after Duccio. It is full of domestic detail: see how the attendant is feeling the bath water before bathing the child, and note Mary’s elderly father outside being told of the birth by an attendant. The interior of the room and the bedclothes are probably very like those of a rich 14th century Sienese lady.

Behind the Duccio Maestà, there are further rooms. The two on the right contain some good painted wooden statues, including a Madonna by Jacopo della Quercia in the first room (the smaller saints on either side are thought to be by his workshop rather than the master’s own hand). And in the end room, there are strikingly tragic figures of Mary and St John on either side of a rather stiff and boring crucifix.

Second floor

This floor can be largely by-passed. Its main room is the “Sala del Tesoro”, the room of the treasure, in which various gold, silver and other objects once in the Duomo are now displayed. Most are dirty and rather tatty looking. There is one large and gruesome casket with a saintly skull still inside. In the glass case in the wall opposite the entrance, the small but dramatic painted wooden crucifix by Giovanni Pisano is worth a glance. And behind the door is a painting of the breast-feeding Madonna that was once in the Piccolomini altar in the Duomo (now replaced by a reproduction). This is a fine work by Paolo di Giovanni Fei of a subject much liked by the Sienese for whom milk had all sorts of symbolic meaning.

Third floor

Immediately at the top of the stairs is the “Sala della Madonna degli occhi grossi” (the room of theMadonna of the big eyes), after the painting in the middle of the room by a very early master usually called the Master of Tressa (after a place where one of the five known paintings by him was found). It was painted about 100 years before Duccio’s Maestà, in a much more primitive style with round Romanesque eyes rather than Gothic almond ones. It hung above the high altar of the Duomo until it was replaced by Duccio’s Maestà, and is renowned as the painting before which the Sienese successfully prayed on the eve of the battle of Montaperti in 1260, their most famous victory over their Florentine enemies.

On the far wall, there are three interesting pictures by Sano di Pietro of St Bernardino, Siena’s great preacher saint. The two on either side of the main portrait show him preaching in front of the Palazzo Pubblico in the Campo, and in front of the church of San Francesco. Note how the practice in those days of segregating men and women in church extends even to informal preaching sessions in the street. On the wall to the left of the door there is a fine set of saints by Ambrogio Lorenzetti

The next two rooms contain later Sienese of little interest, so we suggest you walk quickly through, pausing briefly to admire the large painting of St Paul (in a red robe, reading and perched on a narrow throne) by Domenico Beccafumi. In the background behind St Paul, there are scenes of his original conversion and his martyrdom. The work was painted in 1515 and with its vivid colours and movement is a complete contrast to the more austere and static works in the preceding rooms. Whereas Duccio was the first of the great Sienese painters, Beccafumi was the last. After him, Sienese work became maudlin and second rate.

Facciatone: panorama

At the end of the second room is a small doorway and spiral staircase out to an open air walkway from which another spiral staircase leads to the top of the unfinished façade arch of the planned new cathedral (started in 1335). This is probably the best viewpoint in Siena and truly panoramic, with marvellous views of the dome and roof of the Duomo; of Siena itself; and of the country for miles around.

San Niccolò in Sasso and the side door of the “new Duomo”

Back through the museum and downstairs to the exit, which is through the pretty small baroque church of San Niccolò in Sasso, dating from the late 1500s and early 1600s. Every surface is encrusted with intricate plasterwork and painting.

On leaving the church, turn briefly up the hill to the left to admire the intended side door of the “new Duomo”, one of the most perfect Gothic doorways in existence. Unfortunately, however, the reproduction angels at the top look almost as battered as the originals in the museum.

1996, revised in 2005.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HOSPITAL OF (OSPEDALE DI) SANTA MARIA DELLA SCALA

Siena's ancient hospital, now a museum. It contains one of the best non-religious cycles of frescoes in Italy, and also houses the Etruscan collection of Siena and various other collections. The Sienese authorities have gradually been developing it as the major museum complex of the city.

Opposite the façade of the Cathedral; They keep changing the entrance: it is currently (2023) through the Tourist Office in the neighbouring Palazzo Squarcialuci.. Open daily from 10.30 to 17.00.

The hospital was one of the oldest in Europe, according to legend founded in the ninth century by a poor cobbler called Sorore, although it is only documented from 1090 and the present buildings date from the end of the 13th century. It was not only a hospital, but an orphanage and hostel for pilgrims and the poor as well. It was run by friars and lay brothers and sisters and was immensely successful and wealthy (its money coming largely from bequests and donations, especially from the possibly ill-gotten gains of bankers and merchants, no doubt hoping thus to appease the Almighty). Its success led to jealousies and conflict between the hospital management and the clerics of the Duomo who tried to control it. In 1193 the hospital obtained a Papal Bull from Pope Celestine III giving it its independence from the Duomo. In 1305 Blessed Agostino Novello (see the painting by Simone Martini in the Pinacoteca) wrote statutes for the hospital which served as a model for other hospitals all over Italy and the Holy Roman Empire.

St Catherine of Siena (1347-1380), who spent her early years at home in prayer and saintly contemplation, to the distress of her family refusing ever to go out, was finally persuaded out of the house to nurse the sick at this hospital, presumably on the basis that this was a suitably holy occupation (having taken the plunge, she spent most of the rest of her life travelling through Europe and interfering in the affairs of both Church and State). Later, in about 1400, when Siena was hit by the plague and so many staff were affected that the administration of the hospital collapsed, Siena's other main saint, St Bernardino, then a young man of about 20, took charge of the hospital with a band of companions, apparently nursing the plague victims with great efficiency.

Siena now has a large modern hospital on the outskirts of the city, but Santa Maria della Scala (scala means steps and the hospital is so-called as it is opposite the steps up to the Cathedral) remained a working hospital for some specialities until the early 1990s, and as recently as the 1970s there were beds in the Pilgrims' Hall. The whole building has now been turned into a museum. Behind its Gothic façade, the hospital has been extended and remodelled many times since the 13th century. It now occupies an enormous site, stretching both back and down. .It is still being rearranged and there are often small temporary exhibitions, so the following description of where things are may be quickly out of date.

The Old Sacristy

On the left, after entering through the Tourist Office, there is a room on the right called the Old Sacristy, where there are some piteously damaged frescoes with symbolic scenes representing the Creed (mostly by Il Vecchietta) which must once have been very fine. At one end there is a “Madonna of the Cloak” by Domenico di Bartolo with the religious community being sheltered under one side of her cloak and the lay people under the other.

Pilgrims' Hall (Pellegrinaio)

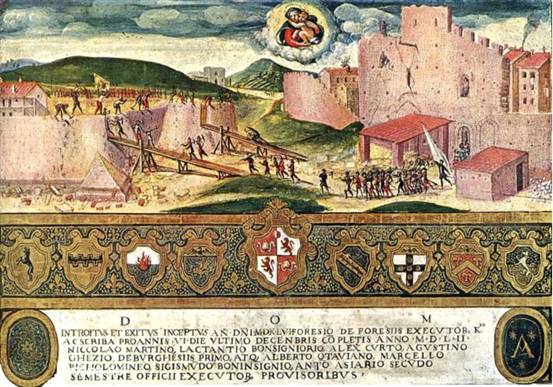

Continue on to the Museum’s star attraction, the huge Pilgrims' Hall where pilgrims were given lodging (and which was a hospital ward until the 1970s). The walls are covered with fascinating frescoes depicting the building of the hospital, but also riveting and rare scenes of hospital life in the 15th century. They were commissioned by a 15th century Rector of the hospital to show the glorious history of the hospital and the good works that it performed. Top artists of the day were employed, including Il Vecchietta and Domenico di Bartolo (the two frescoes at the window end of the hall, however, are later and less distinguished).

The cycle starts on the left-hand end of the wall opposite the entrance with a scene showing the mother of the founder (Blessed Sorore) having a dream of succouring foundlings (shown in her dream going up a ladder to heaven). The rest of the frescoes on this wall show the building and history of the hospital; those on the opposite wall show scenes inside the hospital. All are well explained in the English texts under each fresco. Among the best are:

- The enlargement of the hospital (second fresco on the ‘history’ wall. This is a wonderfully lively scene, with a bishop on a white horse, only just avoiding trampling on an unfortunate workman engaged on the construction of the extension, with various leisured citizens watching from their balconies.

- The nursing of the sick (on the opposite wall). This is perhaps the most fascinating of all, showing a busy ward in the hospital, a doctor examining a specimen on the left; the hospital surgeon examining a young man with a wound in his leg; a friar taking confession from a dying man. The dog and cat squabbling in the foreground are said to symbolise the eternal dispute of physician and surgeon.

Nursing the sick (detail)

- The distribution of alms. The cathedral can be seen through the two doors at the back, and the Rector doffs his hat to an important visitor being shown the hospital. He gives clothes and food to beggars and the poor, elderly and maimed. Alms were given three times a week, with the Rector himself doling them out on feast days. It was ordained that when the poor of good family were brought to the hospital, they should have ‘a servant to make ready their beds and dainty food and wait on them so that they may not suffer from neglect’.

- The reception of foundlings in the hospital and their marriages. The arrival of the foundlings as babies is at top left; below they can be seen being taught by a rather severe schoolmaster with a cane; on the right the grown girls are shown being married, in rather unlikely grand clothes. The hospital reckoned to bring up the foundlings, teaching the boys a trade and the girls domestic skills. The girls were also given a dowry. It is recorded that in 1298 there were 300 children in care; by 1618 there were 1212 foundlings, mostly fostered by families outside, vetted by the hospital. Many died, however; in the 20 years between 1755 and 1774 three-quarters of the 5700 foundlings taken into the hospital failed to survive.

- The Banquet of the Poor, an early soup kitchen.

Old main entrance

On the other side of the Pilgrim's Hall is the old main entrance with - on the opposing wall - a damaged fresco by Domenico Beccafumi (done in 1512) of St Joachim and St Anne, the parents of the Virgin Mary (below).It is his first recorded work, but already has his trade-mark luminous colours and mystical air.

To the right there is a high vestibule with ancient marble tombs in the right wall. That of Giovanni Battista Tondi, who died in 1507, portrays him with his head reposing comfortably on no fewer than three pillows.

Underground floors:Chapel of the Night and Fonte Gaia

Beyond the Pelligrinaio, immediately on the left, there are stair down to the many lower levels od the Hospital. A labyrinth of rooms and mediaeval corridors is gradually being opened and filled with collections brought in from various other museums and buildings. On the first level down, a doorway on the right of the stairs leads to the Chapel of the night, where St Catherine allegedly went to rest and pray at night after her labours in the hospital. There is a rather beautiful 14th century marble statue over the altar, unfortunately marred by unsightly metal crowns. In the room beyond the chapel there is a good tryptich byTaddeo di Bartolo.

All over the Hospital there are fragments of frescoes, giving a tantalising idea of the wall-to-wall decorations that there must once have been.

Fresco in the Hospital showing labourers in a vineyard

Again on the first level down, a large subterranean hall has been given over to an exhibition of the Fonte Gaia, the marble fountain in the Piazza del Campo which now serves as a general meeting point for tourists. The original fountain was by the 15th century Jacopo della Quercia, one of Tuscany's greatest sculptors. By the middle of the 19th century the fountain had got so battered by the elements and events such as the Palio (during an 18th century one a large piece of the fountain was knocked down and damaged) that it was decided to replace it with a marble replica. What remained of the original sat for years on a roof terrace in the Palazzo Pubblico. It has now been moved to the Hospital and is on display at the end of the subterranean hall. Also on display are the plaster casts and gesso models that the 19th century sculptor made as a basis for the present marble copy. The original was in such a bad way that he had to use a fair amount of imagination to recreate della Quercia’s masterpiece; and it is fascinating to see the plaster casts of the original and his models side-by-side.

Etruscan collection (Archaeological Museum)

Siena’s Etruscan collection is also to be found in the archaeological section, further down – keep going until you teach an internal road at the Hospital’s lowest point; the archaeological Museum is through one of the doors off this road.

It is arranged along an intestinal corridor in the bowels of the building that keeps going back on itself but finally brings you out where you started.

It is arranged along an intestinal corridor in the bowels of the building that keeps going back on tself but finally brings you out where you started. The collection is not as big or good as that in Volterra,

and irritatingly grouped mostly according to where the objects were found or from whose collection they came (a lot of the stuff was donated by Sienese collectors), rather than in any sort of chronological or other logical order that would help one understand Etruscan civilization. The signing is also pretty abysmal. But the objects are individually well displayed and lit, and the collection is worth a quick whip round. Like most Etruscan collections, the display is dominated by endless funerary urns and the polished black so-called bucchero pottery that was an Etruscan speciality.

Etruscan funerary urn

Church of Santa Maria della Scala

This church, also known as Santa Maria Assunta, was an integral part of the Hospital and could be entered from inside the Hospital. It is now (2023) treated an ordinary church and is accessed through a door on the piazza in front of the Duomo. The building itself is not particularly distinguished, but it contains some sculpture worth a glance, and an interesting trompe-l'oeil fresco.

In the middle of the side walls are the gilded wooden statues of the Annunciation after which the church is called; they are early l7th century mannerist works, with both the protagonists striking typical contorted attitudes. On the right wall there is also a painted crucifix of around 1300, the oldest object in the church, probably taken from the church that preceded the present building. Further on, still on the right wall, there is a handsome early l7th century organ, one of the earliest instruments of its type. Opposite it, there is a carved "music chapel" of the same period.

The best sculpture in the church, however, is the bronze ‘Risen Christ' (1476) by Il Vecchietta (Lorenzo di Pietro) on top of the main altar. It looks rather out of place perched on top of a false tomb forming part of the heavy baroque altar (although the latter is in its way a handsome piece of work). Indeed, il Vecchietta originally designed it to go on top of a high bronze tabernacle. But the latter was snitched by the Duomo, where it now stands on the main altar of that much grander church. The ‘Risen Christ’ (matched somewhat incongruously by a baroque marble ‘Dead Christ’ in bas-relief at the bottom of the altar) is a beautifully modelled piece of anatomy, reminiscent of Donatello, a marvellous achievement for an artist who was chiefly a painter; it is sad that it is so high up and difficult to see closely. Also on the altar are two handsome long-necked angel candle-bearers (1585) by Accursio Baldi da Monte.

The ceiling of the apse is covered in an 18th century fresco chiefly remarkable for its trompe-l'oeil pillars - from the back of the church the pillars look straight, but if one walks up the steps and goes behind the altar and looks up at them, they are bent almost at right angles.

In the passage leading from the church to the hospital, there is a tiny chapel (cappella) with a 14th century painting of the Virgin and Child by Paolo di Giovanni Fei over the altar.

2000; revised 2010, 2015/6 and 2023

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HOUSE AND SANCTUARY OF ST CATHERINE

The family house of St Catherine of Siena

The entrance is through gates on the Costa di San Antonio, a turning off the via di Sapienza below the church of St Dominic. It remains a religious site. Entry is free and visitors are asked to be silent and modestly dressed.

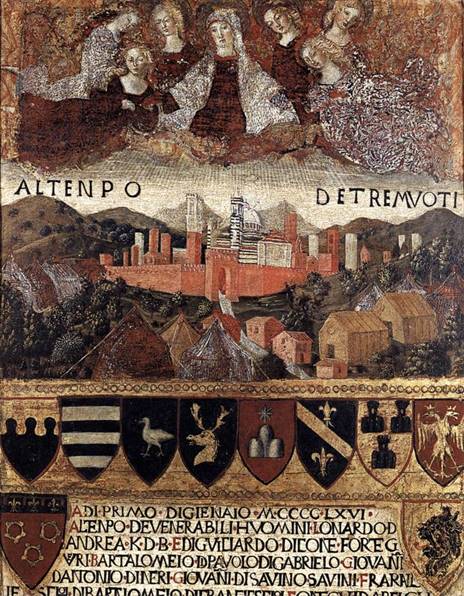

St Catherine of Siena was born in 1347, just before the Black Death hit Siena, the daughter of Jacopo di Boninsegna, a cloth-dyer. Such was her renown that she was canonised shortly after her death and her family house was purchased by the Municipality of Siena in 1466 and turned into a place of veneration.

Over the centuries many changes and additions were made and almost nothing remains of the original house. There is now a whole complex (complessa)with a church and oratories. The wrought iron gates give entrance to a courtyard with an elegant portico on the right, known as the Portico of the Communes (Portico dei Comuni). It was built in the 1940s, just after St Catherine had been proclaimed patron saint of Italy. Every municipality (comune) in Italy contributed the cost of one brick for its construction. In the far right corner there is a rather beautiful travertine wellhead dating from around 1500.

Church of the Crucifix

From the outer courtyard one descends to a smaller covered courtyard. On the right is the “Church of the Crucifix” with a 17th century baroque interior and many paintings of St Catherine and her life, none particularly distinguished. The church was built on the site of what is thought to be the Benincasa family’s kitchen garden to house the painted crucifix over the alter which dates to the 12th century and is Pisan in style. This crucifix used to be in a church in Pisa, and tradition has it that while praying in front of it St Catherine received the stigmata, the five wounds of Christ, on her hands, feet and side. After various vicissitudes, the Sienese had managed to get hold of the crucifix in 1565. It was installed first in the Oratory of the Kitchen and then in the church as soon as the latter was completed.

Oratory of the Kitchen

Opposite the church is the Oratory of the Kitchen (Oratorio della Cucina), thought to be on the site of the Benincasa family’s kitchen. About a century after Catherine’s death, the Confraternity of Saint Catherine (a society of pious lay people attached to the Dominican order) choose this spot as the meeting place for its members. The painting over the alter of St Catherine receiving the stigmata was installed by them. It was painted in 1496 by the Sienese artist Bernardino Fungai on the back wall above the altar. At the time, the crucifix from which Catherine received the stigmata was still in Pisa and very few Sienese had seen it. This explains why Fungai represents the crucifix as a sculpture rather than the painted cross it really is. There are a number of later paintings on the walls showing episodes from St Catherine’s life, of little artistic interest but described in detail on the Sanctuary’s English website.

The grille under the altar allows a glimpse of the remains of an ancient fireplace surviving from the original house. Tradition has it that Catherine, in one of her ecstatic trances, fell into the fireplace while a fire was burning, but was miraculously unharmed. In the sixteenth century the Confraternity decided to enlarge and decorate the Oratory under the guidance of the Sienese painter Bartolomeo Neroni, also known as Il Riccio. He was responsible for several of the paintings on the walls as well as the design of the beautiful blue and gold coffered ceiling (made by the carver and the wooden panelling and stalls, creating a unified whole.

Oratory of the Bedroom

Stairs on the left lead to the Oratory of the Bedroom (Oratorio della Camera). This room was completely remodelled in the 19th century, so is unlikely to bear much resemblance to what it was like in the 14th century. On the right of the entrance one can peer through some pierced iron doors into the cubicle (cubicolo) in which Catherine from childhood would isolate herself for prayer and contemplation. The iron grille on the opposite side hides a stone which according to tradition he used as a pillow.

Oratorio of St Catherine in Fontebranda (or Oratorio of the Tintoria)

Nearby, in via Santa Caterina, there is a small church built after the canonisation of St Catherine in 1461 at the behest of the inhabitants of the Fontebranda district. The old dye works (“tintoria”) of Jacopo Benincasa, the saint's father, and two adjacent houses were demolished to create a space for the church. It is now the church of the Contrada of the Goose (Oca) and is not generally open. It is said, however, to have good frescoes and it houses a particularly beautiful 15th century painted wooden statue of the saint by Neroccio di Bartolomeo.

2022

----------------------------------------------------------------------

PINACOTECA NAZIONALE

Siena's main picture gallery. It contains almost only Sienese painting, but of that it has the finest collection in the world.

Open 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. except Saturdays and Sundays, when it may be open half a day only. Free for EU citizens over 65. To view the paintings in date order, go straight to the second floor of the museum - to which the custodians will probably direct you anyway. The paintings in the museum are constantly being shifted around, so the order may not be as described below. The collection is large and Sienese painting is not always easy for the new-comer to appreciate. So we recommend that the visitor should not attempt to see the whole collection at one go. A floor at a time is quite enough. The collection is displayed over the first (the later works) and second floors (the earlier works). We recommend that you start with the second floor. There is also a top (third) floor with a single room containing the “Spannocchi” collection, a somewhat motley selection of old masters from places other than Siena. We recommend that you visit this only if you have the time and energy after seeing the other two floors (there is nothing on the ground floor).

Sienese painting

Sienese painting started extremely early, and its great period lasted only some 250 years, from around 1300 to around 1550. Throughout the dark ages, although there was painting in Italy, chiefly in the form of frescoes, it was Byzantine in style, showing little originality. For Byzantium, painting was a way of teaching religious stories; artists painted by rule, keeping to set symbolic formulae. The earliest paintings in the Pinacoteca, dating from the 1200s, belong to this tradition.

But in the 1200s, new influences began to be felt and Italian painting began the transition toward naturalism and freedom that was ultimately to lead to Botticelli, Leonardo and the other greats of the Renaissance. Sienese painting never quite kept up, however, with the great Florentines. Whereas in Florence rationalism and a taste for modernity meant that painters were constantly experimenting and evolving, in Siena a mystical streak and a respect for tradition meant that the art stayed stylised and symbolic for far longer. This makes it more difficult for the modern eye to appreciate. But it is well worth the attempt, as there are many beautiful and magical works. In particular, Sienese painting has a decorative and ordered aspect, often with wonderful colours, which the Florentines do not always match.

The works in the museum show how the style evolved from the very primitive, almost childlike works of the 1200s - the earliest to survive - to the more sophisticated but stylised pictures of the 1300s and 1400s, gradually growing more naturalistic, ending with the florid and mannerist paintings of the 1500s - after which Sienese painting declined into mediocrity and sentimentality, never to recover. Most of the works in the Pinacoteca are painted in tempera, powdered pigment mixed with egg to bind it - oils did not become commonly used in Italy until the 15th century, when Flemish painters introduced their Italian colleagues to oil painting.

For details of individual painters, see SIENESE PAINTERS.

The oldest works are on the second floor and the staff will press you to start there.

SECOND FLOOR

Room 1

At the top of the stairs, almost the first painting (No 1) is a ‘Christ the Redeemer in the act of blessing flanked by two Angels’ by an unknown master known as the ‘Maestro of 1215’. This is one of the earliest surviving Sienese paintings. The 6 scenes at the side show the history of the true Cross and its discovery by St Helena. To the right is apainted crucifix of about the same date (No 597). In both works, note the square faces, wide eyes and generally primitive aspect. Paintings of this sort - especially crucifixes - were being produced in various parts of Italy. What is typically Sienese is the "impasto" or raised surface, which was often encrusted with jewels – alas, long ago removed by ancient vandals. On the other side of the room there is a painted wooden statue depicting an almost equally square-faced late 13th century pope. The final painting in this room - a 13th century altar-panel (No 8) by a follower of Guido da Siena - depicts three scenes from the life of Christ: the transfiguration of Christ; his entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday; and the raising of Lazarus. Note the human touches in these scenes - for instance the people clinging to the trees to get a better view of Christ as he comes into Jerusalem - as Sienese art begins to move away from the static and wooden style of the earliest works.

Room 2

Now enter room 2 on the right. This room contains paintings of the later 13th century, with a magnificent Virgin and Child (No 16) on the right, now attributed to Dietisalvi di Speme, but previously thought to be by Guido da Siena (every few years some new expert seems to come along to reattribute these early unsigned works). Guido was the first Sienese painter whose name we know. He is said to have been influenced by the Florentine painter Coppo di Marcovaldo who was captured by the Sienese at the battle of Monteaperti in 1260, Siena's one famous victory over Florence, and made to paint to gain his freedom. Florentine art was already more sophisticated, and the local Sienese doubtless watched their captive at work with interest. Whether or not it is by Guido, this picture is certainly a more zestful and accomplished work than the earlier ones in the previous room, with wonderful colours and a marvellously cheerful Virgin. This is almost the last cheerful Sienese painting; thereafter the Sienese artists tended to cultivate a gloomy and tragic style, beautiful and interesting, perhaps, but depressing for the newcomer used to the more serene and contented Florentines. Note also the beginning of a Gothic influence in the almond eyes of the Virgin. These eyes were to be a characteristic of Sienese painting for the next 100 years.

On the right there is a Virgin with saints (No 7), still thought to by Guido, with more works by him and Dietisalvi in the middle of the room. Also in this room is Guido' s ‘St Peter enthroned’ (No 14), again with a strip cartoon of scenes mainly from the life of the saint down each side of the main panel. The two top ones are the Annunciation (with the Virgin shrinking from the angel), and the Nativity. In the middle on the left there is Christ calling St Peter and St Andrew (charming fishes in the water), and the freeing of St Peter from prison on the right. At the bottom there is the fall of Simon Magus and the crucifixion of St Peter.

Rooms 3 and 4

Siena's greatest painter was Duccio, and Room 3 contains a number of paintings by Duccio or of the school of Duccio, but all are in pretty mediocre condition (for the best of Duccio in Siena, go to the OPA Museum). The central panel of the tryptych at No 28 is, however, particularly worth a glance, with its charming sloe-eyed Virgin and a Child clutching part of her veil. In Room 4, there is a fine crucifix (No 36) by Ugolino di Nerio (a follower of Duccio, active 1317-1327) note the red-eyed Virgin and saint at the corners, the very epitome of the tragic Sienese style.

Rooms 5 and 6

Go through straight through Room 5 (to which we will come back later) to Room 6, which holds the museum's (fairly small) collection of Simone Martinis. Simone Martini, Siena's greatest painter after Duccio, was Duccio's pupil, but he developed a sinuous and elegant style of his own. The best examples of this "international Gothic" style are his "Maesta" in the Palazzo Pubblico and the beautiful Annunciation in the Uffizi in Florence. In Room 6, however, there is a marvellous strip cartoon of the life of Blessed Agostino Novello (a Sicilian holy man who settled at San Leonardo al Lago near Siena and became much revered), who is shown swooping down like an early Batman, saving people from a variety of dangers.

Saving a child fallen from a balcony Saving a child fallen from a hammock

In this room there are also several paintings of the Virgin and Child which may be by Simone Martini - the only one about which there is a fair degree of certainty is that with the bare wood surround. Another delightful painting in this room which may be by Simone Martini is the ‘Madonna della Misericordia’ - Our Lady of Mercy, sheltering the people of the world under her cloak. Some experts claim, however, that it is by Niccolo di Segna (active 1331- 1345), a great-nephew of Duccio. Either way, it is a beautiful, glowing painting.

Now back to Room 5 to admire the magnificent ‘Adoration of the Magi’ (No 104) by Bartolo di Fredi (who painted the ‘Old Testament’ frescoes in the church in San Gimignano), full of movement, with wonderful colours and beautiful detail - note the curls in the hair of the personages; the camels and the bustling Kings' train at the top of the picture; and a stripy cathedral in the Sienese style on the top left. Bartolo di Fredi also painted the very decorative ‘Coronation of the Virgin’ in this room, between the windows.

Adoration of the Magi by Bartolo di Fredi (detail)

Room 7

On the left there is a good ‘Nativity of the Virgin’ (No 116) by Paolo di Giovanni Fei (1344-1411) - note the elderly mother. It was probably inspired by Pietro Lorenzetti's painting of the same scene in the Cathedral Museum. To the right of the painting is a fine wooden statue of St John the Baptist wearing his usual garb of a fleece as an under-garment, with a typically Sienese anguished expression. It is by Domenico di Nicolo dei Cori (1363-1453).

On the other side of the room are paintings by the Lorenzetti brothers, Siena's most distinguished painters of the generation after Duccio and Simone Martini. Both brothers (Ambrogio and Pietro) ceased to be mentioned in documents after 1348, and it is thought that they perished in the Black Death that carried off so many of Siena's inhabitants in that year. Both are more expressive in style than their predecessors, but Ambrogio's work is peaceful and lyrical; Pietro's is more passionate and dramatic. First look at the ‘Madonna and Child’ (No 77) and the ‘Deposition of Christ’ (No 77a) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Although the eyes are still unnaturally narrowed, the faces are chunkier and more human than in the earlier Sienese paintings. Note also the tremendous feeling of sorrow and anguish in the lower scene of the Deposition. Opposite, still by Ambrogio, is a ‘Madonna and Child with chaffinch’, the bird held rather uncomfortably by one wing. On the other side of the wall, there is an assumption by Ambrogio, with a very serious looking Madonna. In the same style, also on the other side is a Madonna by Pietro Lorenzetti.

Rooms 8, 9, 10 and 11

Go past rooms 8, 9 and 10 (the latter being nothing but a small baroque chapel), and stop in Room 11, where there is a good ‘Annunciation with Saints Cosmo and Damian’ (No 131) by Taddeo di Bartolo (1362-1422). Note that the eyes are now back to a more normal shape after some 100 years of stylized almond eyes. God the Father is shown on the top left with the Holy Ghost as a dove sliding down a ray of light to impregnate the Virgin - although truth to be told, she already looks rather pregnant. There is also a fine crucifix in this room.

Rooms 12 and 13

In Room 12 there are two fine paintings by Giovanni di Pao1o (1399-1482), with lots of movement and emotion. The ‘Crucifix with Saints’ (no 199) includes San Galgano plunging his sword into the stone. In Room 13 there are two wonderful Presentations of Christ at the Temple, with marvellous high priests, probably wearing mediaeval Jewish robes. The stylised tragic faces of the early paintings have now disappeared completely, and every face has its own strong and very human character. The temple, however, is still an idealised Gothic building, and it will be a few years yet before buildings too become naturalistic.

Rooms 14 and 15

In Room 14 theMaesta (No 432) by Matteo di Giovanni (circa 1430-1495) is very much of the Botticelli period, with a more delicately featured Virgin and softer colours. Also noteworthy is a Madonna and Child (No 286) by the same artist, with a happy smiIing Madonna, and angels chatting at the top. There are some good paintings byFrancesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502); in particular a Madonna and Child with saints (No 288) and anAnnunciation (No 277) on the right on entering.

This was a period when a more realistic style was creeping in, although still fairly idealised by our standards. TheNativity (No 437) also by Francesco di Giorgio Martini shows how buildings have become naturalistic, with a romantic ruin and a real thatched roof stable replacing the fantastic jewelled Gothic halls in which earlier Nativities were housed, and rocks alive with flowers and animals have replaced the earlier elaborate tiled floors. In Room 15, theAdoration of the shepherds and saints (No 279) by Pietro di Domenico {1457-1506) again shows something like a real stable.

Rooms 16, 17 and 19

Rooms 16 and 17 are largely taken up by the works of Sano di Pietro, a factory production line of stereotyped polyptyches. He really only comes into his own only in the predellas beneath the main panels, many of which have lively and interesting scenes. Room 19 is full of large but mostly undistinguished paintings. We suggest that you walk fairly quickly through these rooms and descend to the floor below for something completely different.

THIRD FLOOR: SPANNOCCHI COLLECTION

For a change from Sienese painting before going down to the firsrt floor, go up the small stairway that leads up to the third floor, which is devoted to a small collection of non-Sienese paintings formed in the 17th century by a Sienese nobleman. Most are undistinguished, but there is a good painting of the Nativity by Lorenzo Lotto (c1480-1557). There are also some other works of the Venetian school and a number of Flemish paintings.

The Tower of Babel, one of the Flemish paintings in the Spannocchi collection

FIRST FLOOR

This floor has a number of good works by two very different 16th century artists - Beccafumi (1486-1581) andSodoma (1477-1549), Siena's last two painters of note. Sodoma (his real name was Giovanni Antonio Bazzi) came from the Piedmont but spent much of his life in Siena. His work follows on from the more naturalistic artists on the floor above (he was also influenced by Leonardo da Vinci), with delicately drawn scenes, attractive landscapes, graceful figures and soft colouring. Beccafumi represents the quite new style of mannerism, with figures striking elaborate "mannered" attitudes. Beccafumi is noteworthy, however, above all for a marvellous use of colour and light, creating dramatic and often visionary effects. Occasionally, however, he veers into distressing sentimentality, or into an effect which does not quite come off, as when he gives butterfly wings to angels.

Rooms 20, 21, 22 and 23, and the Sculpture Room

Go straight through Rooms 20-22 (these rooms have some nice paintings but not as good as those further on). In Room 23, pause only before No 102 on the wall opposite the door - a Visitation with Saints by Pietro di Francesco Orioli (14581-96). It portrays a charming scene with most of the participants having lively conversations with each other, caught in mid-word.

Bowing as you pass to Queen Elizabeth I on the wall of the stair-well, turn right into the Sculpture Room. The room is worth a visit if only because of the marvellous views of Siena and its roofs – the untidy forest of aerials that once festooned them has now been replaced with neat terracotta-coloured satellite dishes. But the room also has some interesting early sculptured panels. There is a key (in Italian) on the table. No 5 (3 panels on the right wall, bottom row by the window) shows scenes from the life of the Blessed Gioacchino Piccolomini: first ringing at the door of the monastery which he decides to join as a young man; then having an epileptic fit and upsetting a table, but with everything on the table remaining miraculously on it; and finally having another epileptic fit during Mass, but again without upsetting anything.

Rooms 27, 28, 29 and 30

These are devoted to Beccafumi and followers. Look particularly at the Beccafumi tondo of the Virgin and Child in Room 27 (she looks as though her reading has been interrupted); and in Room 28 at the Birth of the Virgin (No 405), showing her as a startlingly grown-up baby already sucking her thumb, the whole scene with wonderful light effects.

Rooms 31-36